The latest study by the Force Science Institute has produced two surprising findings of importance to trainers, street officers, and police attorneys.

1.) Some suspects lying flat with hands hidden under chest or waist can produce and fire a gun at an approaching officer faster than any human being on earth can react to defend himself

2.) The angle sometimes advocated as the safest for approaching a prone subject appears, in fact, to be potentially the most dangerous

In testing five different angles of weapon exposure and attack, FSI researchers discovered that the overall average time that elapses between the instant a prone suspect’s first movement can be seen and the discharge of his pointed weapon is less than two thirds of a second.

One subject in one of the firing postures monitored was able to move so fast that the gun in his hand could not be detected until the moment it discharged. The fastest subjects produced the weapon from under their chest and fired it upward and ahead — the line of approach taught by some trainers as being the most protective for officers.

One trainer who witnessed the testing exclaimed: “Wow! I knew suspects could be fast, but I didn’t know they could be that fast!”

“This study is the first of its kind,” lead researcher Dr. Bill Lewinski told Force Science News, “and it scientifically establishes that the desperate urgency officers often feel to control a prone subject’s hands is fully justified.

“If hidden hands are not controlled immediately and the suspect is armed and decides to shoot, an officer is likely faced with an insurmountable challenge to react fast enough to prevent what could be a fatal attack.”

Research Motivation

Common street sense dictates that a live suspect lying on his belly with one or both hands hidden under his body poses a potential threat because of his possible access to a concealed weapon. However, Lewinski points out, “all training and tactics for dealing with this real-life field problem have been based on anecdotal experience, impulse, and supposition, not on any scientific foundation.”

Moreover, in recent years a number of controversial, high-profile encounters have been captured on news video, showing officers using what appeared to be extraordinary force to expose downed suspects’ hidden hands during capture and arrest.

“Media critics and other civilians, including jurors and force review board members, seemed unable to understand the officers’ sense of urgency in some of these cases,” says Lewinski, FSI’s executive director. “Strikes with batons or flashlights delivered by officers trying to gain control of resistant suspects’ hands were sometimes interpreted as malicious outbreaks of rage and vindictiveness.

“It became clear that we needed to scientifically explore the threat level presented by prone suspects with hidden hands because of the significant legal, training, and survival implications inherent in this subject.”

Sgt. Craig Allen of the Hillsboro (Ore.) PD, the on-site coordinator for the resulting FSI study, put it this way: “Let’s have the facts. Once we know for certain what we’re dealing with, we can understand, explain, and train.”

Testing Setup

After some preliminary testing at FSI headquarters in Minnesota and at the Northeast Wisconsin Technical College to refine methods, Lewinski and his research crew last February performed a four-day series of rigorous experiments in Oregon with the help of Hillsboro PD’s training unit.

One at a time, 39 volunteers — a mixture of male and female LEOs and college students, ranging in age from 19 to 32 and with varied fitness and agility levels — proned out on mats on the floor of a vacant commercial building. Each held a .22-cal., J-frame S&W revolver loaded with black-powder blanks under their chest or waist.

Each volunteer fired 25 rounds, producing the gun and shooting 1 round as fast as possible 5 different times in each of 5 different directions: from the chest up and ahead, to the left rear, and to the right rear, and from waist level to the left rear and to the right rear. Each was told to shoot as if trying to hit an officer center-mass approaching from those various directions at a distance of about 10 feet.

Three high-definition video cameras positioned at 3 different angles filmed the action. These time-coded tapes were then synced and meticulously analyzed under the direction of safety-management researcher and doctoral candidate Madeleine Gonin at the Ergonomics Laboratory at Indiana University.

Some of the participants were also filmed by the Canadian Discovery Channel. “Each of the subjects moved in a somewhat different way, depending on what seemed most natural and fastest to them,” Lewinski says.

Surprising Findings

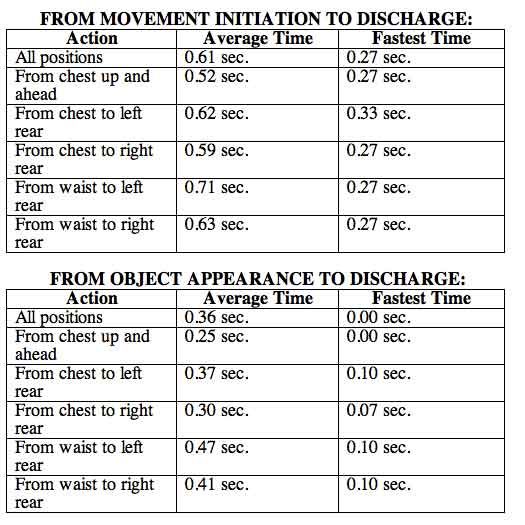

From Gonin’s analysis of various elements in nearly a gigabyte of video footage, 2 measurements are the most significant, Lewinski explains.

One is the amount of time that elapses from the moment a subject starts his or her first, detectable pre-attack movement (usually a shifting of feet or hips) until the gun discharges. The other is the time from when any part of the gun is first visible until it fires; that is, from the time “something” from under the suspect’s body — not even yet identifiable as a weapon — is first captured in a camera frame.

“All the time lapses recorded are startlingly fast — much faster than we imagined before the experiments,” Lewinski says.

Specifically:

Disturbing Interpretation

Disturbing Interpretation

“It’s important for officers to know how quickly an attack can unfold, because in terms of reaction time to sudden threats, a targeted officer is very likely to be significantly behind the curve,” Lewinski says. “This is consistent with findings from other Force Science time-and-motion studies.”

He points to the fastest times in which the research subjects were able to fire after some part of their gun first became visible. For some, there was no time gap; the gun could not be seen until it discharged. At most, only 1/10 of a second elapsed. Even the averages, lengthened by inclusion of the slowest shooters, ranged between ¼ second and less than half a second.

“There is not a human being in the world who can react before the discharge in those time frames, even if they are expecting a threat and have their gun up and ready!” Lewinski declares. “Even before the object coming into view can be recognized as a gun, a shot is off.”

Nor can an approaching officer expect to be alerted by a suspect’s pre-attack movement in time to preempt the threat. Even the slowest average time from initial movement to discharge is less than ¾ second. “Seeing a suspect’s feet or hips start to shift to provide a physical base for bringing a gun out is of virtually no value in a swift attack,” Lewinski says. “There’s not enough time to comprehend what’s happening and react.”

Most surprising, Lewinski says, were the results when test subjects produced a gun from under their chest and fired to the front and up at about a 45-degree angle.

“Some trainers and officers believe that approaching a downed suspect toward the head provides the least vulnerability because lifting the torso up to shoot takes more effort,” Lewinski says. “But ironically the fastest shooting times were achieved by subjects attacking toward that direction. In reality, the chest can be lifted and a gun pushed out with very little dynamic movement.

“Average times both from motion to discharge (0.52 seconds) and from appearance to discharge (0.25 seconds) are lowest in that position. And in the worst case from an officer’s perspective, the gun is not at all visible until the instant it fires (0.00 seconds).”

Legal and Training Implications

The scientific documentation of how quickly deadly threats can materialize from prone suspects could be helpful in explaining to force reviewers why officers sometimes feel compelled to use vigorous physical tactics in gaining control of hidden hands, Lewinski believes.

The legal impact will be discussed in greater detail by Capt. Scott Sargent of the LAPD, an attorney and certified Force Science Analyst, as part of an official paper on the study to be published by the researchers in a peer-reviewed professional journal. We’ll advise you when this is available, expected to be in spring 2011.

As to tactical training implications, Lewinski shares a couple of preliminary observations:

1.) In parsing the study data, it appears that prone suspects tend to be slowest in delivering gunfire when they are shooting toward the rear on the side opposite their gun hand. Thus in this study, in which most participants were right-handed, the slowest time averages from motion or weapon appearance to discharge occurred when subjects were shooting to the left rear with a gun hidden at waist level.

“This is because they had to turn more to free the gun arm from under their body,” Lewinski explains. “Some subjects, in fact, had to roll almost onto their back before being able to shoot. Consequently, approaching toward a prone suspect’s feet may be marginally safer — if anything can be considered safe in coming up to a downed suspect whose hands are hidden.”

2.) Keeping the suspect uncertain as to the approaching officer’s location may be the best tactic for buying reaction time or forestalling an attempted attack.

“This may require deviation from the normal contact/cover approach,” Lewinski explains. “The contact officer, who normally would be giving commands, can remain silent while the cover officer, ideally behind some protective barrier, issues verbal directions. This may allow for a stealthier approach by the contact officer and put the element of surprise more in that officer’s favor.

“The less information the suspect can gather about the officer’s location and angle, the slower he’s likely to be in getting on target.”

Lewinski stresses that “these are only tentative suggestions at this point. We are looking now to the training community for tactical strategies that can be tested with additional research.”