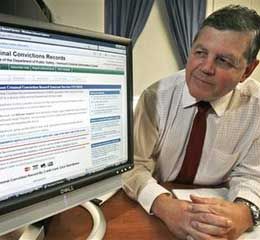

Deputy Director Bruce Parizo of the Vermont Crime Information Center looks at the Web page for Vermont criminal conviction records at his office in Waterbury, Vt., Thursday, Dec. 11, 2008. (AP Photo) |

By John Curran

Associated Press

WATERBURY, Vt. — Worried your daughter’s new boyfriend might have a nefarious past? Want to know whether the job applicant in front of you has a rap sheet?

Finding out can be a mouse click away, thanks to the growing crop of searchable online databases run directly by states. Vermont launched its service Monday, and now about 20 states have some form of them.

The Web sites provide a valuable and timesaving service to would-be employers and businesses by allowing them to look up criminal convictions without having to submit written requests and wait for the responses. And they’re popular: Last month alone, Florida’s site performed 38,755 record checks.

But the Internet debut of information historically kept in courthouses in paper files can magnify the harm of clerical errors, expose states to liability for mistakes and spell new headaches for people who’ve long since done their time, only to have information about their crime bared anew.

“It’s unfortunate in that it threatens what I see as the uniquely American ideal of being able to start over, after you’ve paid your penance, to go to a new community without the blemish of your crime and starting a new life,” said Kevin Bankston, a staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco-based group focused on civil liberties online.

Vermont’s system, which costs $20 to query one person’s records, includes information on criminal convictions dating to the 1940s. It taps into the Vermont Criminal Information Center database used by law enforcement agencies, which state officials claim is “cleaner” - has fewer mistakes - than courthouse records or the data sold by private information brokers working off those records.

All you need to make an inquiry is a person’s name and date of birth, and a credit card to pay the fee.

If the query finds a record, the system lists the date of conviction, charge, sentence and venue. It won’t show the original charge filed, or give information about the victim or the circumstances of the crime.

Also inaccessible, according to officials, are records that have been expunged or sealed. And people can report mistakes in the records on them and ask for changes.

Agencies that deal with “vulnerable populations” - children, seniors, the disabled - can use the database for free, avoiding what is now a seven-to-10 day waiting period for the same information through the mail.

Allen Gilbert, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Vermont chapter, opposed the state’s move, in part because it sets up a two-tiered system of records - one set at the courthouse and another online. The online system gives only a slice of information about the cases, he said.

“There might be something about the conviction that if you looked at the court record, you’d better understand about what happened and what’s behind the conviction. It would give the person whose record you’re looking at a chance to have the full story explained, rather than just the end result,” Gilbert said.

Michael Donoghue, executive director of the Vermont Press Association, questions whether the information in the online database yields meaningful conclusions about a crime or a criminal.

“The problem with some of these services is that they do not provide a true picture concerning the person,” Donoghue said. “There may be other arrests that were made at the time, but in the interest of justice or in plea bargains, cases get dismissed. So somebody who was on a crime spree that commits 16 burglaries across several counties but pleads to only one case looks the same as the college student who, while intoxicated, breaks into a store on the way home from the bar.”

Putting the records online also exposes people - and potentially states - to harm or liability if there are mistakes.

“It’s not simply defamation in the traditional sense,” said Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a research center in Washington, D.C. “It’s denying someone an employment opportunity if someone says `I’m not going to hire the guy because he has a drunk driving conviction’ and it’s the wrong person. The state bears the responsibility for accurate data,” Rotenberg said.

Michigan notifies users of its Web site that its system is name-based, making it inherently less foolproof than fingerprint-based searches.

“We say the only way to ensure (getting the right person’s record check) is a fingerprint search,” said Shanon Akan, a spokeswoman for the Michigan State Police.

Most states charge a fee for the service. Some make available all the records on file in a case, including the original charge, even if it’s not what the person was convicted of.

“You get everything we have, except anything ordered sealed or expunged by a court: descriptive data of the person physically, everything about the charge and the arrest, regardless of whether it’s dismissed or the charges weren’t pursued, the court action, information on incarceration,” said Martha Wright, chief of user services for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, which maintains that state’s online criminal histories Web site.

Brian Poe, chief executive of ClearMYrecord.com, an automated online tool that helps people apply for expungement, clemency or pardons, says online rap sheets make life more difficult for people with records.

“The challenge facing ex-offenders who’ve repaid their debt to society is already daunting enough, on the employment side, without them having to worry they’ll be charged over and over again in the court of public opinion,” he said.

“It’s like a scarlet letter that can be used as a tool.”