| The relationship between the media and law enforcement is often adversarial. Reporters appear to seek the sensational elements of a crime story, often to the detriment of the police, and officers tend to be uncooperative with journalists they seem to instinctively mistrust. Not so with “The Badge,” a new series presented by a San Francisco Chronicle reporter/photographer team embedded with the SFPD. Kudos to the Chronicle for pursuing this series and to the officers who willingly put themselves in the media spotlight in the hopes of helping civilians develop a better understanding of life behind the badge. You’re putting a human face on “the police,” which will benefit us all.

|

By John Koopman

The San Francisco Chronicle

SAN FRANCISCO — After dark, when the tourists have gone back to their hotels and families are having dinner, the streets of Chinatown are quiet. Two men walk down a deserted alley, lit by dim streetlights and open apartment windows.

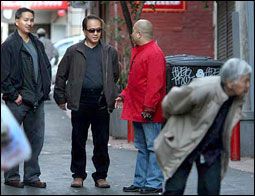

Inspectors Jameson Pon (left) and Henry Seto (center) walk the streets of Chinatown and chat with residents. (Chronicle photo by Brant Ward) |

The smell of twice-used cooking oil wafts through the still air and hangs on the sound of mah-jongg tiles clicking on linoleum tabletops. Bursts of shouting and laughter erupt now and then as someone wins a bet, or loses. The sounds emanate seemingly from every other window and door.

“Gambling is a way of life in Chinatown,” says Inspector Henry Seto, a 23-year veteran of the San Francisco Police Department. “You can’t stop it. It’s not even worth it to try.”

Seto’s not here to worry about low-stakes card games, however illegal they may be. He and his partner, Inspector Jameson Pon, work the Asian gang detail for the SFPD. They work the streets collecting information on the various gangs that focus on Chinatown, but spread out into the Richmond and Sunset districts, too, along with the Asian populations out there.

Seto and Pon are native sons of Chinatown. They grew up there, they speak the language, they went to the Chinese school classes after school and weekends growing up, and now they patrol the neighborhood trying to keep gang activity to a minimum.

Inspectors Jameson Pon (left) and Henry Seto talk with a young man about a recent crime in Chinatown just outside an illegal gaming parlor. (Chronicle photo by Brant Ward) |

They are the only two San Francisco police officers working in the Gang Task Force who focus on Asian gangs. Which is ironic, because the task force was originally developed in response to the gangs of Chinatown. The incident that sparked it all was known as the Golden Dragon massacre. In 1977, a feud between the Joe Boys and Wah Ching ended in a shootout that left five people dead, including two tourists, at a restaurant by that name.

At one point, the Gang Task Force had 25 officers assigned to Asian gangs. When Pon joined the unit 13 years ago, there were about 15 officers. Now, it’s just the two.

“We could use four more,” Pon said. “Every time Henry or I catch a case, we’re off the street. A lot of stuff goes on out on the street, and we’re inside doing paperwork.”

Their job involves talking to people. A lot of people. They chat up store owners, old men at Portsmouth Square, kids on the street corners.

The gambling dens are prime territory for Seto and Pon. A lot of the people who hang out there know what’s going on in the criminal underworld, or are part of it.

Inspectors Jameson Pon (left) and Henry Seto examine the entrance to an underground gambling parlor before entering. (Chronicle photo by Brant Ward) |

They ring the electric buzzers on the front gates of the gambling dens, and then climb down narrow steps to the rooms lit by fluorescent lights. There, under the watchful shrine to Kwan Kung, the Chinese god of war who is also something of a patron saint for gamblers, men and women play cards and try to ignore the two cops in their midst.

“That guy’s in a gang,” Seto says, nodding toward a tall young man sitting above a table watching the play. “He’s on probation, so we can visit him and search him any time. Those guys in the corner are (gang) associates.”

There are 48 officers in the Gang Task Force, but the bulk of the work is directed at the street gangs of Bayview, Hunters Point, Ingleside, the Western Addition and the Mission. Those gangs are responsible for a lot more murder, mayhem and drug sales than are the Asian gangs.

The Chinatown gangs focus on extortion, drugs and prostitution. There is violence occasionally, but it remains mostly self-contained. Chinatown is a much more closed community than the rest of San Francisco, and a lot of people have come from other countries where they did not trust the police. The trick for Seto and Pon is to persuade people to talk.

In recent weeks, both officers have made arrests involving alleged extortion plots. In one case, they said, three men were arrested after they tried to extort protection money from a Richmond District bar. When the owner refused to pay, the men returned around closing time and trashed the place.

“The owner only knew them by their street names,” Seto said. “We knew who they were. A couple of days later, we got a call that they were in a video cafe, so we went over and picked them up.”

Pon’s case involved a man who owed some gangsters too much money. The man left the country, but the people he owed tried to get the money from his father. When the man didn’t pay up, someone set off an M-1000 firecracker on his windowsill. The M-1000 has the explosive power of about a quarter of a stick of dynamite; it shattered the window. That got his attention, but not in the way the gang members predicted.

“He was really afraid after that, which is why he didn’t mind telling us about it,” Pon said.

Seto and Pon work pretty well as a team. Seto is the talker. He knows everyone in the Chinese community, and he never stops talking to community activist and criminal alike.

Pon is the guy who puts everything together. He takes the information Seto gathers, along with his own and stuff from cops on the street, and tries to make connections. To make a bust, to build a case for prosecution, or to help out officers in other units who have cases touching on the Asian gangs.

Seto is 55. He was born in Hong Kong and came to the United States when he was about 6.

He walks past the Ping Yuen housing projects and points to a door on the second floor. He lived there as a child. Several San Francisco cops lived in that same housing project, he says. So did some of the most notorious gang members in Chinatown.

Pon is 48. He grew up a few blocks away. Not the projects, but it wasn’t exactly Pacific Heights, either.

“A lot of guys I hung around with ended up in gangs,” he says. “I knew the guy who planned the Golden Dragon massacre.”

Between them, Pon and Seto have a lot of history in the neighborhood. Now they walk the streets looking for kids who are in gangs, or likely to join them. They’re like a couple of cranky old Chinese uncles, stopping teenagers on the street and asking hard questions.

“Why aren’t you in school?” Seto asks one youth who looks to be 15.

“School’s out,” the boy responds, shocked to have to explain it.

“Why aren’t you doing your homework, then?” Seto asks. “Go on. Go home and stay out of trouble.”

Copyright 2007 San Francisco Chronicle