The first order of business was to go back to scene of the shooting. It wasn’t a sentimental thing. He just had to go back to where it happened to see what he could have done differently, what he could remember. The fence, there. The dumpster, there. The alley where he sped his vehicle in reverse, flawlessly.

After re-analyzing it all he came to a conclusion: He had no regrets. He had reacted perfectly.

Twelve days earlier, Sioux City officer Kevin McCormick was fresh out of roll call and ready to hit the streets around 1500 hours. He had been with the department 15 short months, and liked where he was at. As he drove his cruiser he thought about the upcoming three day weekend. I like what I do. I wouldn’t mind if they called me in to work on one of my days off, he thought.

McCormick saw that a hit-and-run had been called in and was anticipating that dispatch would assign him to the call, so he made his way toward the West end where the accident occurred, when he passed a vehicle heading in the opposite direction that caught his eye: a female passenger without a seatbelt.

As he spun his squad around to pursue, the car made a quick right and sped up. The car slowed at a stop sign, then hit the gas and made another right, then a third, more or less driving in a full circle.

McCormick called it in — a Nebraska plate, which wasn’t rare for Sioux City — and activated his emergency lights. The vehicle turned down an alley infamous for gang activity.

Ready to Run

The vehicle came to a stop, as did McCormick, and he undid his seatbelt. He’d been taught to exit his vehicle as quickly as possible at a stop, so he threw his vehicle into park and cracked his door when he saw a passenger in the stopped vehicle fumbling around and jumping out of the car.

“I thought he was going to run. I was preparing for a foot pursuit. Then the door swung open, he stepped out, and raised a .22 caliber pistol,” recalls McCormick. “My first instinct was, ‘This guy has a pellet gun’. We find a lot of airsoft pistols in the area. So I’m thinking he’s out of his mind if he thinks he’s going to shoot at me with a pellet gun and I’m not going to return fire.”

McCormick threw his squad into reverse and ducked, flying backward through the narrow alleyway as the man fired. On the third or fourth round, McCormick felt a sting above his right eye. It didn’t feel the way he had expected a bullet to feel. More like the sting of a rubber band snapping on his forehead, and his vision in his right eye had suddenly worsened.

McCormick had distanced himself 75-100 feet and the shots had stopped. When he peered up over the dash he saw occupants in the vehicle ahead, but couldn’t tell if the gunman was inside or if he had fled.

“Shots fired,” McCormick told dispatchers. “I’ve been shot in the head. Suspect is a black male, wearing black, six-foot-one, 220 pounds, carrying a .22.”

Listening to the call now, McCormick can hardly believe how calm he was as he described the gunman to dispatch.

“I don’t know what I can attribute that to. Maybe training, maybe just survival instincts, I knew I needed to get that information out there for this guy to be caught.”

His sergeant came on the radio and told him to stop pursuing; other officers would take it from there.

“That was really tough for me to handle,” says McCormick. “I wanted to continue. If I had been so injured that I couldn’t think clearly, I would have gladly said ‘okay’ but I didn’t feel that way. But, I had to listen to my command staff.”

Up until that point McCormick still wasn’t certain what had hit him above his right eye. It wasn’t until weeks later that he learned that the full slug that embedded itself in his forehead was just shy of causing serious damage. When a dose of anesthetic and a surgeon chipping away at the slug didn’t do the trick, a neurosurgeon was called in to drill it out.

He stayed awake through the night. Not just from the excruciating headache, but the anticipation of a phone call and an enthusiastic “We got him!” But that call didn’t come until five days later.

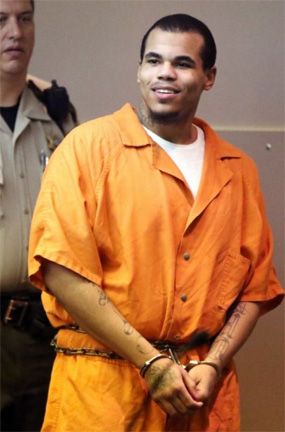

Jamal Dean, a 22-year-old man wanted on burglary charges, was arrested without incident in Texas, and pleaded guilty in McCormick’s shooting in exchange for dropping burglary charges. McCormick was there as he entered his plea.

“He came into the courtroom with a big smile on his face,” said McCormick. “Like this was a cool thing to be a part of. It wasn’t something I’ve taken personally. You can’t. In this line of work if you can’t let something like that roll off your back, you won’t last.”

Dean is now serving a 25-year sentence with the possibility of parole in 17 ½.

The Notoriety of a Cop Killer

It’s McCormick’s theory that Dean intended to kill him before his arrest, so that he would enter the corrections system as a cop killer, receiving instant notoriety and rank. It’s also McCormick’s belief that many people worked to keep Dean’s location under wraps for those five days he was missing, including his father.

|

| Jamal Dean is pictured smiling in court. Dean is now serving a 25-year sentence with the possibility of parole in 17 ½. (Photo courtesy Sioux City Journal) |

Dean’s father approached McCormick at the hearing to offer an apology, which the officer had a hard time accepting.

“I understand the need to protect your son, but at some point you have to draw the line,” he said, reflecting on the day in court.

In true police form, the court overflowed with officers from all over who came to show their support for their wounded rookie. But Dean had his share of supporters, too.

“They all had these T-shirts that said ’Keep your head up’ and I remember thinking how funny that was. If I had kept my head up at that moment that he fired, I’d be dead right now.”

Support for McCormick came in so many forms: stacks of ‘Get Well’ cards from all over, food and flowers from family. The night of his shooting 250 officers from South Dakota and Nebraska were out searching for Dean. An e-mail from a deputy in Tennessee who’d survived a shot to the head that said simply, “Let’s talk.”

“I can talk about the incident all day long, every detail, with no emotion. But when I talk about the people and their support, that’s when I get choked up.”

Perhaps the most amazing support came from the community, and not just for McCormick, but for the Sioux City police as a whole.

“People wave at us when they see us out now. It was like they finally saw what we were up against. It’s a pretty cool thing.”

McCormick has maintained a level-headedness throughout the incident that continues to amaze. From calmly describing his aggressor to dispatch, to his injury and miraculous recovery, to the ‘unchanged’ man he is today.

McCormick says he didn’t have a near-death experience. That night doesn’t even haunt him.

“It’s not a pride thing. I just believe the circumstances were right. I got hit in the right spot by the right caliber weapon.”

McCormick was out of the hospital in less than 24 hours and back on patrol in 12 days, like nothing had changed.

“This hasn’t changed my outlook on anything. I’ve always been cautious, maybe in some cases overly cautious. I’d much rather draw down on someone than hesitate, so I don’t feel like I’ve changed any on that end.”