By Matthew Roy, The Virginian-Pilot (Hampton Roads, Va.)

The growing number of mentally ill people locked up in Hampton Roads jails is prompting searches for innovative solutions, from special courts to police programs.

One approach, in Memphis, Tenn., has drawn interest from Virginia and is spreading to departments across the country. It emphasizes bringing mentally ill people into treatment - not jail.

Members of the Memphis police crisis intervention team get 40 hours of training on mental health and conflict resolution, then regularly handle calls involving disturbed people. They work closely with a hospital that accepts people for psychiatric assessments around the clock.

By contrast, mental health training for Hampton Roads officers typically consists of several hours in a police academy, with occasional refresher courses. No 24-hour psychiatric drop-off facility exists. Officers who think somebody should be detained must enlist a mental health professional and a magistrate - a process that can take hours. They may have to transport the person to a distant mental hospital.

It is quicker to make an arrest, said David L. Simons, a former police chief who is assistant superintendent of Hampton Roads Regional Jail in Portsmouth.

In Memphis, fewer than 1 percent of calls handled by the police crisis intervention team result in arrest, compared with an estimated national average of 20 percent on similar calls, said Randolph Dupont, a psychologist who has worked with the program.

“There’s a lot of individuals standing on a street corner who may be cursing and may be yelling and may be going in and out of traffic,” said Maj. Sam Cochran, the program coordinator. “Each of those would be an infraction - disorderly conduct, disturbing the peace, or something of that nature. But who really cares if the individual goes into the criminal justice system? The public wants that person off the street.”

Officer James Smith takes a break from patrolling the streets of Memphis to check on Joseph, a man he has dealt with in the past. Team members often establish a rapport with some of the mentally ill people in their precincts.

The Memphis model stresses peaceful resolution of confrontations. Officers say they rarely resort to force.

Not long ago, a man went door to door in a Memphis neighborhood, holding a box-cutter blade to his throat. “I need to die,” he told startled residents.

Police found the man and began talking with him as he sat on a curb, clutching the blade. He was dirty, possibly homeless.

Officer Lee Allison, a team member, opened his trunk and retrieved a fearsome-looking weapon called the SL6 launcher. It has a stock like an assault weapon, a fat black barrel and a revolving six-shot magazine. It fires nonlethal rubber rounds the size of a stubby cigar. Just the sight of the SL6 usually inspires cooperation. Another officer tried to reason with the man.

Each time the man raised the blade to his throat, Allison would aim the SL6. Finally, the man tossed down the box-cutter and officers took him to the hospital.

Such dangerous calls are what spawned the crisis team.

In 1987, a man slashed himself 100 times with a knife and then lunged at officers, who shot and killed him. Facing a public outcry, police and mental health advocates created the team. Today, 233 officers - about a quarter of the city’s uniformed patrol officers - are members.

They take the lead in situations involving disturbed people, and their approach can be different. Officers are able to spot and address the underlying human aspects of a situation, Cochran said.

On an autumn evening, shards of glass crunched underfoot as Officer James Smith, a team member, stepped into a small apartment.

The man inside had called police to say his girlfriend had attacked him. She smashed the front window on her way out.

The shaken man volunteered that he was a recovering alcoholic and drug addict. He suspected his girlfriend had been using crack. She had scars from self-mutilation on her arms. “Her daddy warned me about her,” he lamented, his head in his hands.

Smith asked, Are you thinking of hurting yourself? The man said he suffered from depression. He had been suicidal, but wasn’t now.

Smith pressed. Is there a gun in the apartment? Yes, the man said.

“It’s going to be all right,” Smith assured him. “But I don’t want you by yourself tonight.”

The man picked up the phone and arranged to spend the night at a friend’s.

Setting up a similar program in Virginia isn’t easy.

Some Virginia Beach officials considered the Memphis program years ago. At first, it looked promising, said Deputy Chief James A. Cervera. But police realized the city had no psychiatric drop-off center, and also noted potential barriers in state law.

Nonetheless, some departments in Virginia are adopting crisis intervention models. Roanoke County started a similar program in 2000. Police from several rural New River Valley departments in western Virginia finished their training earlier this year.

Portsmouth officials are discussing the idea, too. Meanwhile, many mental health and legal professionals in Hampton Roads try to intercede when they see sick people headed for jail.

On the Peninsula, mental health workers sometimes go to court to secure the release of inmates, said Charles A. Hall, executive director of the Hampton-Newport News Community Services Board.

That has happened in Virginia Beach, too. Mental health workers also have steered people from the jail to psychiatric hospitals and mental health supervision in the community.

Norfolk has launched the region’s first formal court program intended to address the problem.

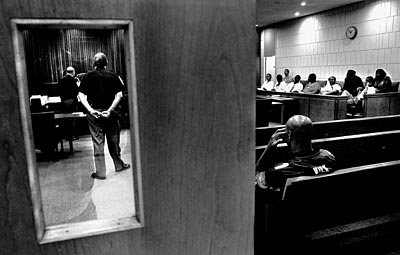

Participants in Norfolk’s new mental health court wait to discuss their progress with Circuit Judge Charles E. Poston.

Norfolk Circuit Judge Charles E. Poston beamed as a young man approached the bench one afternoon.

“I hear you got a job,” Poston said.

“Temporarily,” the man answered with a shrug.

“It’s a job, isn’t it?” Poston persisted.

Each Tuesday, nonviolent offenders with histories of mental illness appear before Poston on charges such as drug possession and violation of probation. Most have been jailed for at least a short while; some have been locked up time and time again. The court offers them a chance to regain their freedom, health and stability. At first, they must attend weekly.

The judge often asks about their families and how they’re feeling.

“One of the big things is you’ve got to keep taking your medication,” Poston often says.

Modeled on similar courts around the country, the program began in the spring and has grown to include more than 20 defendants. It operates hand-in-hand with mental health services.

Defendants get a tailor-made treatment plan designed to keep them healthy and on the right side of the law.

Along with advice, Poston dispenses consequences. One day, a woman told him why she skipped court the previous week. Poston raised his eyebrows. “What makes you think you can make those decisions without my permission?” he asked. He ordered her jailed for a week, and deputies led the stunned woman away.

Wilford Anderson entered Norfolk’s new mental health court program after being caught with $5 worth of cocaine. He failed drug tests, though, and was sentenced to two years behind bars.

Wilford Anderson was one of the first defendants selected for the court. A longtime drug abuser, he had been caught with $5 worth of rock cocaine in his pocket, along with a knife. By some estimates, three of every four mentally ill people in the criminal justice system abuse alcohol or drugs.

Anderson, 48, initially arrived early for court, sporting dress slacks, leather shoes and a tie. With an amiable smile, he told Poston he was a singer, a starving artist.

Like most of the defendants, he pleaded guilty and his sentencing was put off. He was placed on supervised probation and was forbidden to drink or use drugs. He was to be tested. He was to live with his mother, and he was ordered to comply with treatment recommendations, including those for his substance abuse.

Outside of court, Anderson said he wanted to be clean. But he also spoke fondly about cocaine. Word reached Poston, who subsequently confronted Anderson from the bench.

Anderson answered timidly. Cocaine helped him lose weight and stopped the voices he had heard, he told the judge. Poston frowned. He warned Anderson that cocaine was the road back to jail.

A week later, a contrite Anderson read in court a poem he had written, titled “I Apologize.” I throw myself on the mercy of the court, And pray to God for those who have fought To make America a drug-free nation And those that are strong enough to resist temptation.

“I appreciate that,” Poston told him. “I think we all do.”

Drugs proved Anderson’s undoing, though. He repeatedly failed tests. He missed court. In October, while other defendants watched, he was led into court in a striped jail jumpsuit. Poston sentenced him to serve two years.

Most in the program have fared better. Some have found full-time jobs.

One young man eagerly recounted his week to Poston: He skipped a party and found out later the police raided it. He was getting along better with his parents. He had agreed to meet with a career counselor.

He described a recent job interview at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. The interviewer kept looking at his waist. He figured he’d blown it - he had worn a leather belt.

Poston laughed and told him to keep looking.

The court and a few other programs around Virginia are being watched as promising means to keep the mentally ill out of jail. Though the state has not provided money, officials are interested, said Dr. James Reinhard, the state mental health commissioner.

A statewide group of mental and legal professionals recently made several recommendations to state officials. Among them: take a census of inmates with mental illness, share innovative means of dealing with them, and establish a model police crisis team, possibly based on the Memphis program.

A crisis team alone can’t do the job; a patchwork of community programs is needed, said Memphis’ Maj. Cochran.

The state must invest more in programs that promote mental health, not only responses to crises, said Valerie Marsh, the executive director of the Virginia chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Local community services boards that deliver services are chronically starved for cash, she said. Norfolk’s board eliminated outpatient mental health counseling in 2003 because of budget cuts.

In Memphis, team members sometimes take a special interest in the people they meet, establishing bonds and developing rapport.

In the hardscrabble southeast precinct, Officer James Smith, crisis team member, was having a busy afternoon. He questioned a man who had threatened a woman, recovered a gun from a muddy ditch and calmed feuding families at a housing project.

Between calls, he spotted a lanky man on foot.

“Hey Joseph!” the officer shouted.

Joseph, headed away, didn’t look back and quickened his pace.

Smith brought his Dodge 4-by-4 around and pulled in front of Joseph, who broke into a grin when he saw the officer.

Joseph was a local high school basketball star who became mentally ill in college. Now he was doing better but still had occasional “episodes.” Smith wanted to catch up with him.

When Smith stepped out of the car, Joseph awkwardly embraced him.

“How’s Momma doing?” the officer asked.

Good, Joseph said. He added that he was doing well himself - keeping in shape and staying busy.

That’s good, Smith said. They shook hands. Joseph strolled off down the leafy street.