By Jill Leovy

The Los Angeles Times

LOS ANGELES — It was among the most brutal Southland homicides in recent memory: On a sunny Sunday afternoon last fall, two men jumped out of an SUV and set Marcial Sanchez on fire, in full view of a crowd on Cesar Chavez Boulevard in East Los Angeles.

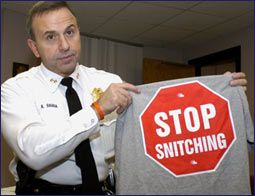

Police are increasingly seeing witnesses being intimidated. (AP Photo/Don Heupel) |

The 52-year-old factory worker was engulfed in flames and burned over 70 percent of his body. He died hours later at a hospital.

No one who saw Sanchez’s killing reported it to police. The hush was so complete that for months the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department considered the case a possible suicide.

The slaying, like so many drive-by and walk-up shootings, was committed in a brazen, conspicuous way precisely because it was designed to stop witnesses from coming forward, authorities said.

“They definitely have people terrified,” said Sheriff’s Sgt. Shawn McCarthy.

The episode stands out as an especially gruesome example of the massive problem of witness intimidation. Over and over in Los Angeles County, killers commit such daylight shootings to cement their control over the streets.

“They show the average citizen that they [the killers] can do things and get away with it,” said Sheriff’s Lt. Al Grotefund.

The problem is a factor in no less than “all gang-related crimes,” he added.

Gary Hearnsberger, head deputy of the district attorney’s hard-core gang division, said reluctant witnesses are so ubiquitous in the world of felony gang cases that practitioners like him have a hard time quantifying it.

“We deal with it every day. ... It’s like breathing air for what we do,” he said.

The reluctant witness is the primary reason that the rate of solving most 2007 homicide cases in Los Angeles County stood at about 41 percent at year’s end, law enforcement experts say, leaving the majority of killers unpunished.

Police agencies and the district attorney’s office relocate witnesses regularly for safety, a step that Hearnsberger says is an effective way to protect people. But many witnesses still balk.

“Witnesses are terrorized and afraid to come forward,” he said. And perpetrators try to keep it that way. “There are clearly homicides where they are trying to send messages,” he said.

When it comes to building rapport with potential street sources, sincerity is everything. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made. When it comes to building rapport with potential street sources, sincerity is everything. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made.  | ||

| — Charles Remsberg Senior Police1 contributor | ||

Sanchez, an immigrant from the Mexican state of Puebla, was the father of three adult children and grandfather to four young children.

Detectives say he owed as much as $23,000 to shady lenders who were charging higher and higher interest rates, and they consider it possible that the debts may have made Sanchez the target of some gang, organized crime ring or loan shark.

The message might have been, “You burnt me for money, I’ll burn you,” said homicide Det. Q. Rodriguez, an investigator on the case.

Sanchez and his second wife worked together at a tortilla factory. They were on their way to pick up a co-worker in East L.A. before the night shift that Sunday, Oct. 7, detectives said.

A short distance from the co-worker’s house, Sanchez asked his wife to drop him off at a liquor store. He wanted to buy a beer for himself, he said, and a Gatorade for her.

She continued to the co-worker’s house. Sanchez entered the liquor store, came out with the Gatorade in his hand, and stood near the Arco gas station in the 3500 block of Cesar Chavez Boulevard, waiting for his wife to pick him up.

It was just after 6 p.m., still daylight. The street was crowded with people. Sanchez was wearing his white factory uniform.

A black GMC Yukon-type SUV with “spinner” hubcaps pulled up and double-parked near him. Two men, both Latino, jumped out. One grabbed Sanchez and poured a container of what detectives say probably was gasoline over him; the other flicked on a cigarette lighter.

Sanchez burst into flames. The assailants leaped into the SUV, which made a U-turn and sped down an alley.

Sanchez’s uniform was on fire. Panicking, he ran to the corner, where passersby began trying to help him. At that moment, his wife and the co-worker pulled up. His wife tore off her blouse, ran up to him and used it to douse the flames. Sanchez was burned from his head to his knees, red in some places, skin sloughing off in others.

He was conscious and standing when paramedics arrived. He was described as talking vaguely of “los muchachos,” the boys, and how they had somehow gotten him wet before he was burned.

Sanchez died at County-USC Medical Center some 12 hours later, before he could be transferred to a burn center.

When the detectives were assigned the case, it was unclear why he had burned. They had a smattering of conflicting evidence -- and nagging doubts. Why, they wondered, would Sanchez kill himself in such an unusual way?

As many as 20 people were on the street at the time. But at first, not one of the people they interviewed would admit to seeing the attack. Instead, witnesses insisted that they had seen nothing, or that Sanchez had simply burst into flames out of nowhere. Some seemed afraid even to be approached. “They said, ‘Ooh man! Don’t let anyone see you talk to us!” Rodriguez recalled.

Finally, though, secondhand reports led the detectives to a witness, who, after lengthy prodding, reluctantly provided an account that corroborated other evidence suggesting not suicide, but homicide.

Eventually, the investigators developed enough of a description for a sheriff’s artist to complete sketches of two suspects. The county coroner’s office has determined that Sanchez’s death was a homicide.

Sanchez’s children, who were called by his wife who reported that “someone had set him on fire,” initially thought only one of his arms had been burned.

They described him as a hard-working and responsible man, quiet with strangers, who had come to this country 25 years ago, employed continually from the day he arrived. He never learned English. They were heartbroken over his death and begged witnesses to come forward, “so that we can have justice,” said one daughter, 26.

The three siblings said they thought their father might have been a random victim. But they also acknowledged that he owed large sums of money to informal lenders. It is not clear to whom he owed the money, why he borrowed it or what he used it for. All three children asked that their names not be used. They were afraid, they said — just like everyone else.

The community in which the homicide occurred is especially ripe for predators.

Many of Sanchez’s neighbors are illegal immigrants in desperate need of money and unlikely to go to police to report attacks against them. “All the ingredients for extortion,” McCarthy said.

But if Sanchez’s killers are not caught, they will have demonstrated that their methods work, detectives said.

Cracking the case could mean breaking the grip these underworld characters seem to have on a whole community of largely poor, marginal and powerless people, Rodriguez said.

The detectives will accept information from anonymous tipsters and said witnesses will be relocated for safety with state funds and aided in finding jobs.

The killers “sent a message. But I’d like to send a message too,” Rodriguez said. “My message is that one day we will find who did this. We will.”

Copyright 2008 The Los Angeles Times