Since the ’92 riots, the department has sought to improve tactics and community relations. But lessons learned failed Tuesday’s test.

By Andrew Blankstein and Richard Winton, Times Staff Writers

The Los Angeles Times

LOS ANGELES, Ca. — The May Day immigration protests Tuesday began as a textbook moment for LAPD community relations.

Top department officials had meetings with march and rally organizers weeks before to help plan the route, set the ground rules and make sure there would be no trouble.

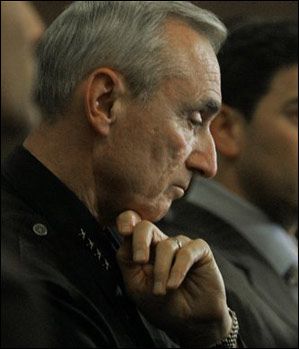

Los Angeles Police Chief William Bratton listens as city leaders discuss issues related to the May 1 immigration rights rally, at a City Hall news conference last Friday. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon) |

Police officers appeared relaxed and could be seen chatting and laughing with protesters as they moved up Broadway to City Hall earlier Tuesday.

But six hours later, the situation turned dark.

A group of agitators began throwing plastic bottles and other objects at police during a late afternoon rally at MacArthur Park.

LAPD officers in riot gear quickly moved in, firing scores of foam projectiles and swinging batons at marchers and reporters.

Both scenes reflected the two key lessons the Los Angeles Police Department learned 15 years ago after the riots.

One was about “community policing,” the idea of working with activists and neighborhood groups to reduce tensions.

The other was “rapid deployment,” the swift and powerful quelling of unrest before it escalates.

It was a particularly painful lesson for the department, which was severely criticized for not acting quicker in 1992 to put down early looting and mob violence such as the beating of a truck driver at Florence and Normandie.

“The May Day melee shows how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go,” said Joe Domanick, senior fellow in criminal justice at the USC Annenberg Institute who wrote a book about the LAPD.

Indeed, the response to the protests has emerged as a serious black eye for a department that has won much acclaim since LAPD Chief William J. Bratton took office in 2002 for a significant drop in crime across the city.

The tough-talking Bratton aggressively targeted homicides and other major crimes — particularly in troubled inner-city neighborhoods.

Those efforts yielded results, but the May Day violence is one of several videotaped incidents of questionable police behavior.

The 1992 riots erupted after a jury acquitted white LAPD officers in the videotaped beating of black motorist Rodney King. For minorities who have for decades complained about police misconduct, the video images from the incident in MacArthur Park “reopen old wounds, regrettably,” said L.A. Police Commission President John Mack.

“At the very least, this is a major, major setback in our attempt to build the relationship between the Police Department and the community of color,” said Mack, a veteran civil rights activist.

Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez (D-Los Angeles) was more blunt, saying the videotaped confrontation with reporters and marchers will leave a lasting — and negative — perception of the LAPD.

“This is the most embarrassing incident that we have witnessed in a very long time in Los Angeles,” he said. “I wasn’t sure if I was watching something going on in Los Angeles or a Third World country.”

How did it get to this point?

The May Day marches began as a collaboration between organizers and police — the kind of community interaction the LAPD has strived for since the 1992 riots.

Police met with the organizers weeks before to plan the route and kept in touch to estimate crowd size. On the day of the march, far fewer participants than expected turned out — and the LAPD helped when organizers decided to delay the march in hopes of attracting more people.

Problems occurred at the end of a second march on MacArthur Park. Some protesters — whom officials describe as “agitators” not affiliated with the march sponsor — threw debris at officers. Police then decided to clear the park. Videotape shows officers firing 240 “less-than-lethal” rounds as well as hitting people with batons. About 10 reporters and protesters suffered mostly minor injuries.

Crowd control has long bedeviled the LAPD. Forty years ago, the department was criticized for its violent suppression of antiwar protests in Century City. After the 2000 Democratic Convention in L.A., the city paid more than $4 million to settle lawsuits filed by protesters and reporters who said the LAPD had violated their civil rights.

But law enforcement experts point out that the department faces a tough balancing act. As the L.A. riots demonstrated, they said, violent mob rule can spread quickly if not quelled.

After the Lakers’ NBA championship victory in June 2000, LAPD officers mostly stood down as revelers roamed the streets around Staples Center.

Some troublemakers torched two LAPD patrol cars, damaged dozens of vehicles on dealer lots and threw trash cans and road construction barricades through the windows of nearby businesses. Afterward, the department was criticized for not acting more aggressively.

Indeed, a few have come forward urging the city not to rush to judgment about the May Day incident.

“If the Los Angeles Police Department does not stand its ground and enforce the law, we will have anarchy,” said Ted Hayes, a longtime downtown activist who has spoken out against illegal immigration.

But Merrick Bobb, who serves as the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors’ watchdog of the Sheriff’s Department, said law enforcement can control crowds while protecting rights.

“Respectful and constitutional policing is not the polar opposite of effective and responsive policing in crowd control situations,” he said. “Both can be achieved through preplanning, training and a clear understanding of protected 1st Amendment speech and news-gathering and 4th Amendment prohibitions against excessive force.”

Paul Wertheimer, a crowd control consultant who studied last year’s May Day demonstration in Los Angeles, said it appeared that police this week made several mistakes in trying to restore order.

He said officers appeared to have overreacted, moving too strongly against the entire crowd, instead of pursuing the troublemakers throwing rocks and bottles. “Condemning the entire crowd because of the acts of a few provocateurs creates a dangerous situation for everybody,” he said. “They needed to separate the elements of the crowd who were causing problems as quickly as they could, but it doesn’t appear as if that happened.”

Like police agencies throughout the nation, “the LAPD is struggling with how to deal with these types of situations,” Wertheimer said. “It’s a complex issue that requires a lot of training by police.”

But some believe Tuesday’s action only reinforces the image the LAPD has long fought of having “warrior cops” who are quick to confront.

“This was not an episode where officers felt cornered, reacted out of fear or instinctively in the face of a threat,” said Domanick, of the Annenberg Institute. “This was a very methodical, well-planned and coordinated attack on people. It was appalling how out of proportion their reaction was to the situation.”

Times staff writers Tami Abdollah and Matt Lait contributed to this report.

Copyright 2007 Los Angeles Times