After Scrutiny Over Safety, Taser Rebounds With Profits, Good Outlook

The Associated Press

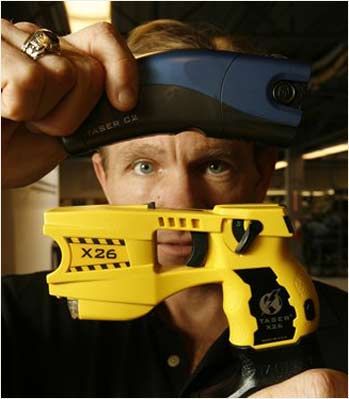

Stephen Tuttle, vice president of communications at TASER International, holds up the TASER X26, bottom, and the new TASER C2, top, at headquarters in Jan. 2007, in Scottsdale, Ariz. The TASER X26 is the standard police issue and the new TASER C2 is the latest consumer launch. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin) |

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. -- Taser International Inc. co-founder Tom Smith has never understood the hostility directed at his company’s stun guns.

Taser’s electroshock weapons were created to reduce injuries, Smith said. Police no longer need to hit people with billy clubs or shoot them with bone-cracking rubber bullets.

“I figured the people that were going to lead the parade for us would be Amnesty International and the ACLU,” Smith said. “Instead they’re our biggest detractors.”

Human rights groups continue to warn that Tasers may cause heart attacks. But two years after its stock price plunged under the weight of intense government scrutiny, wrongful death lawsuits and a storm of negative press, Taser is back on the rise.

The sleek, battery-powered weapons are now strapped to officers’ hips in more than 10,000 of 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States. Internationally, Taser sales have exploded, with products now sold in 44 countries.

Though its stock remains flat and well below its peak in 2004, analysts have big expectations this year. Taser has boosted profits each of the past four quarters as Smith aggressively defended his weapons in the media and the courtroom. Taser paid for research into the health risks of stun gun shocks, and, on occasion, has sued coroners who included Tasers as a possible cause of someone’s death.

Matthew McKay, an analyst with Jefferies & Co., predicts Taser will be Wall Street’s top performing stock in 2007. McKay expects Taser to record $105 million in sales this year and its stock to more than double in value as investors realize the company isn’t going away.

“You’ve got a company that a lot of people have written off,” McKay said.

In May, Taser will begin selling a smaller version of its police weapons to the public. Available in a variety of colors including metallic pink, the Taser C2 can stop people from 15 feet away “allowing you to protect yourself and your family from a safe distance,” according to the brochure.

Taser also plans to expand its product line to the military, a market with a potentially huge interest.

Smith said he envisions a day when U.S. Marines can shock insurgents from 100 feet away using a wireless Taser tucked into a shotgun shell. He sees national borders and embassies protected by a mine-like Taser device that shoots electrically charged darts at people who come too close. Neither of those products is on the market yet.

“The military is a big part of where we think the business is going to go,” Smith said.

Inside Taser’s futuristic glass-and-steel headquarters in Scottsdale, employees still bristle when someone brings up Amnesty International or the day in 2005 when the company’s reputation began to unravel.

Smith, a lifelong sci-fi buff, founded Taser with his brother, Rick, in 1993, in hopes of ushering in a new generation of weapons. He figured people would eventually see Tasers as he did -- as science’s best attempt at the Star Trek “phaser” gun, which could incapacitate a target without killing.

“We can send a man on the moon, talk on cell phones, all of these things. But really the technology to defend yourself, which is one of those needs back to the caveman days, hasn’t really advanced other than inflicting more pain,” he said.

The brothers hired Jack Cover, an aging inventor who had dabbled in electroshock weapons. He called his invention the Thomas A. Swift Electric Rifle (Taser) after a series of adventure novels.

The company developed a number of different stunning devices in the 1990s, including an unwieldy and expensive “Auto Taser” stun club that fastened to steering wheels to shock would-be car thieves.

In 2003, Taser started gaining momentum on Wall Street as the Smiths peddled their M26 and X26 stun guns to police. The guns shoot two barbed darts attached to wires that deliver up to 1.3 watts of electrical current for several seconds, temporarily immobilizing people from a safe distance.

“Sales were going through the roof,” Smith said. “Virtually no one was competing with us.”

But on Jan. 6, 2005, a letter from the Securities and Exchange Commission rolled into Taser corporate offices. The federal agency said it was looking into the company’s safety claims and a $1.5 million sale that appeared to inflate the company’s sales to meet annual projections.

Taser had previously brushed aside claims from human rights groups that its weapons were potentially lethal. Now the government was going to take a look.

“I was infuriated,” Smith said. “We knew the perception was ‘Wow, they must have done something wrong.’”

Taser’s stock plunged 30 percent the following day to $22.72 per share. Within a few months, it was worth $8.09.

Shareholders weren’t happy. They filed class action lawsuits, claiming company executives misled shareholders about Taser’s business practices and the guns’ general safety. Taser eventually paid $20 million to settle with its shareholders while not admitting fault.

Arizona Attorney General Terry Goddard also started asking questions about Taser’s safety claims in 2005. His office ended its inquiry several months later after Taser changed its promotional materials.

Instead of “non-injurious,” Taser’s Web site now characterizes its guns as “generally safe.”

The SEC completed its investigation into Taser at the end of 2005 without recommending any enforcement against the company. Another federal investigation, this one by the Department of Justice, is ongoing.

Steve Tuttle, Taser’s vice president of communications, said he’s tried to learn from the experience.

The company’s public information staff now encourages police departments to publicize incidents when stun guns are helpful. Taser sends reporters e-mails whenever the stun guns helped stop suicide attempts or prevent brawls, or when the company has video of its guns being used in a positive way.

Taser’s PR department also has armed itself with stacks of research reports -- some of which the company paid for -- showing that Taser stun guns pose only limited, if any, health risks.

Taser contends that its weapons have never been the primary cause of somebody’s death, and so far nobody has been able to prove the company wrong in court. Taser boasts it has won 37 straight wrongful death or injury lawsuits, with the judge either dismissing the case or ruling in favor of Taser.

“It’s extremely difficult” to prove Taser responsible, said John Dillingham, a Phoenix attorney who lost a wrongful injury lawsuit against Taser in 2005.

Dillingham represented a retired Maricopa County sheriff’s deputy who said he was injured by a Taser in a training exercise. Lawyers for Taser said the stun gun wasn’t to blame for the deputy’s hurt back, pointing out he was suffering from osteoporosis.

The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Department later became one of Taser’s biggest clients.

Dillingham said it would take a victim who had been in perfect health to beat Taser in court: “A teen or someone in their 20s who is in a crowd and who is inadvertently hit with a Taser and dies,” he said. “There’s no drugs. There’s no alcohol. That person just died.”

Meanwhile, human rights groups say they’ve watched Taser’s rise with dismay.

Amnesty International estimates that 232 people have died in the United States and Canada after being shocked by Tasers, but its researchers admit the tally is totally unscientific, based mostly on media reports. Taser says it has offered to settle the matter by co-sponsoring research on the health risks of stun guns, but Amnesty has refused.

“It’s a matter of huge dispute as to whether or not the Tasers directly cause deaths, and there are many cases where the coroner has not found a link,” said Angela Wright, a researcher in London who collects information on stun gun deaths for Amnesty International.

Tuttle, who has spent much of last year burnishing the company’s image in the media, said a lot of people don’t realize this.

“In 2005, it felt like I was in a boxing match with one glove behind my back,” Tuttle said.

“It was brutal,” he added. “Now we’re not getting bombarded everyday with a crisis.”

Amnesty International: http://www.amnesty.org

ACLU: http://www.aclu.org

Taser: https://www.taser.com

unding