By Dan Elliott

Associated Press

(AP Photo) |

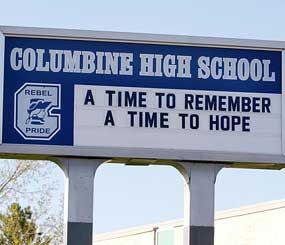

| Related News Report: Columbine, 10 years later |

LITTLETON, Colo. — Teenage gunmen spilled the blood of children before Columbine - in Alaska, Arkansas, Mississippi and Oregon. After Columbine, more blood was shed in Minnesota and California, in Germany and Finland.

But none of those tragedies cast a shadow as long or dark as the rampage at Columbine High School, where 13 people were gunned down 10 years ago Monday.

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, seniors at the suburban Denver school, detonated homemade bombs and opened fire with shotguns, a rifle and a semiautomatic handgun on April 20, 1999. They killed a teacher and 12 students and wounded 23 others before committing suicide.

The massacre shocked the country like no other. It was the worst school assault in American history at that time, and it came in the wake of a half-dozen others. It played out on live television, watched by millions. And it represented the violent destruction of a cherished American idea: that schools in the suburbs and the countryside were havens of peace and safety.

“It’s the iconic shooting,” said Katherine S. Newman, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University. “It defined the social category of a rampage school shooting.”

—

Americans were on edge about school violence before Columbine. During the previous two years, at least 16 students and teachers had died in school shootings in small American cities and towns: Bethel, Alaska; Pearl, Miss.; West Paducah, Ky.; Jonesboro, Ark.; Edinboro, Pa.; Fayetteville, Tenn.; and Springfield, Ore.

All the killers were teenage boys, except one, an 11-year-old boy.

Without those earlier shootings, Columbine would have been seen as “a terrible, bizarre aberration, not to be repeated,’” said James Alan Fox, a criminology professor at Northeastern University.

Columbine created fear that things were spinning out of control.

“So much of the angst, the anxiety and response, was already in motion when Columbine happened,” Fox said.

—

Harris and Klebold had planned to detonate bombs inside Columbine’s packed cafeteria at lunchtime and then pick off fleeing survivors, the sheriff’s investigation showed. Most of their bombs failed to explode, but the gunmen began firing, killing some students outside the school and others inside.

They had plotted the attack for months, but their reasons remain a matter of speculation. Psychologists and journalists who pored over investigative reports have published books portraying Harris as a cunning, hateful psychopath and Klebold as a deeply depressed and suicidal teen.

Investigators released thousands of documents under court orders prompted by media lawsuits, but other evidence has never been made public. That includes depositions by the gunmen’s parents. A judge in 2007 ordered those statements sealed for 20 years.

—

Traumatic images of the Columbine shooting played out on TV screens across the nation: frightened students streaming out of the school, a wounded boy struggling to escape through a window, ranks of heavily armed SWAT officers waiting for permission to go in.

The coverage went on for hours. SWAT teams didn’t enter Columbine until 47 minutes after the attack began - a delay that was harshly criticized and led to new law-enforcement tactics nationwide. Five hours passed before deputies declared the school under control.

Cable news channels were just spreading their wings and live coverage of breaking stories was coming into its own, said Al Tompkins, a former TV news director who teaches classes in broadcast and online news at the Poynter Institute.

“Unlike some of the shootings that were only covered in the aftermath ... millions of Americans watched as it unfolded, which obviously has a much greater effect on the American psyche than if you watch some footage on the 11 o’clock news,” said Fox, the criminologist at Northeastern.

—

Compounding the horror was the shock that the shootings happened in a fairly typical American suburb.

“We couldn’t understand how this could happen in any place other than urban schools,” said J. William Spencer, an associate professor who teaches sociology at Purdue University.

The illusion of safety had begun to weaken with the Alaska school attack in early 1997. At Columbine, it collapsed.

“It was no longer possible to disassociate - ‘Oh, that’s something that happened at some faraway town in some other state,’” Muschert said. “People started to have the perception that ‘it could happen here.’”

—

Harris and Klebold’s rampage made a lasting impression on other troubled young men.

Twenty-three-year-old Cho Seung-Hui, who killed 32 people at Virginia Tech University two years ago Thursday, left a video referring to “martyrs like Eric and Dylan.”

Matthew Murray, 24, who killed four people that year at a church and a missionary training school in Colorado, compared himself to Harris and Cho in an Internet posting.

Eighteen-year-old Pekka-Eric Auvinen, who in 2007 killed eight people at a high school in Tuusula, Finland, wrote e-mails about Columbine and put posts on a Web site dedicated to Harris and Klebold.

Like Harris and Klebold, all three shooters committed suicide.

“Subsequent shooters who have been fueled by a kind of competitive urge cite Columbine first, foremost and always,” Newman said.

—

Survivor Patrick Ireland, the student seen on TV escaping through the second-floor library window, is weary of the school being a benchmark for tragedy.

“I hate it when people say, ‘Oh, another Columbine-like (tragedy) or Columbine-esque tragedy,’” said Ireland, now 27 and married and working for the Northwestern Mutual Financial Network.

“Columbine is a school. The shooting was an event that happened and a lot of people have been able to overcome so many things from that,” said Ireland, who has regained mobility with few lingering effects from gunshot wounds to his head and leg.

Columbine’s hold on the American psyche will weaken when today’s adults, who remember the attack so vividly, give way to a new generation, Newman said.

At Columbine High School, the generational shift has already begun. This year’s graduating seniors were 8 years old at the time of the massacre. The freshmen were 4.

Cindy Stevenson, superintendent of Jefferson County Public Schools, which includes Columbine, said the events of 1999 don’t seem to weigh on Columbine today.

“I can only tell you my impression as I watch the kids,” she said. “It feels like any other high school in our district.”