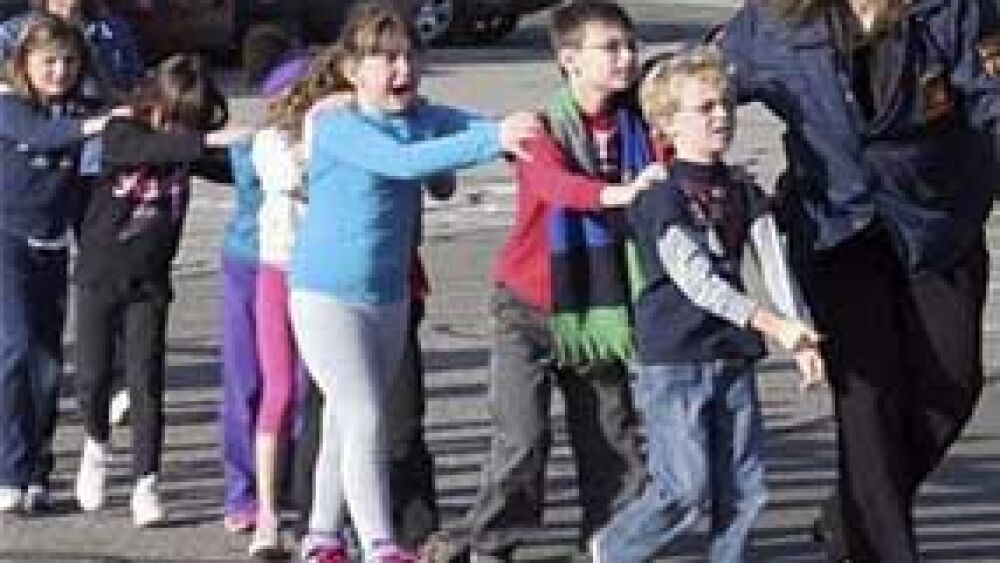

One year ago — December 14, 2012 — a deranged gunman entered the elementary school of a bucolic Connecticut town, murdered the two unarmed school administrators who attempted to stop him, and then proceeded to slaughter 20 beautiful little children and four other other adults.

Shortly after hearing the sound of approaching police sirens, Adam Lanza killed himself.

That worthless little coward should have started — and consequently ended — his day with his own suicide. Instead, he began by murdering his mother as she slept in her bed. He then drove to Sandy Hook Elementary and committed his unspeakable crime.

How Far Have We Come Since Newtown?

I contend that 12/14 might be the 9/11 for parents and educators of young children — and for police and security professionals charged with protecting those innocent lives.

The “it can’t happen here” mentality should have been permanently and totally dismantled after Columbine, Beslan, Virginia Tech, NIU, Oikos, and other school attacks.

But it wasn’t.

As a nation, we should have learned from Red Lake Senior High, Parkway South Middle, and Cleveland Elementary.

But we didn’t.

Hell, the Bath School disaster in 1927 claimed the lives of 38 elementary school children, but it’s too much to ask the average person in 21st century America to have such a detailed understanding of our history.

No, if any appreciable change in our collective thinking about active shooters in schools is to happen, Sandy Hook Elementary will likely have been the catalyst.

This raises two questions:

1.) How far have we come in the year since the Sandy Hook school massacre?

2.) How hard are we willing to work to prevent such tragedies in the future?

Hardening the Target

In the aftermath of the Newtown attack, some schools began to examine the installation of Makrolon Hygard bullet-resistant polycarbonate sheeting on first floor windows — the gunman had shot his way into SHES.

Some schools decided to put air horns in the fire extinguisher cases, so that teachers could sound the alarm of danger — not just the administrators in one office of the school, as was the case with Sandy Hook.

Some police agencies began performing an elaborate shell game of squad cars parked in front of schools — whether or not there was an officer inside became the gamble for any potential attacker.

During IACP 2013, I watched as Abington (Pa.) Police Chief Bill Kelly and Assistant Superintendent Leigh Altadonna presented some easily implemented ways in which officers and educators can work to prevent an active shooter from killing kids in schools.

In Abington, cops have patrol rifles, breaching tools, and tourniquets. Teachers have been trained in the police tactics they can expect to see as well as practical emergency care to help save lives of injured students before police and EMS arrives on scene.

There is a protocol for the two-way exchange of information about incidents that might be precursors to violence. Police officers and school administrators even carry identical smartphones, pre-programmed with each other’s phone numbers.

Every classroom has a folder full of materials for teachers to review the police/school response procedures, and every squad car has a tube in the trunk in which is stored a set of laminated floor plans, pictures of the schools, and other tactical information.

There are police LMR radios strategically positioned in the schools so that when an event does occur, teachers can provide real-time intel on the location of the shooter, the number and location of casualties, and other vital incident information.

Do these measures make Abington schools truly hardened? Of course not, but those are tremendous steps in the right direction.

Vetting, Training, and Arming Staff

Want to really harden a target? Put a good guy with a gun in the place.

As news of the Sandy Hook massacre unfolded, I set about writing a column asking whether or not we should be vetting, training, certifying, and arming American school teachers.

I didn’t (and don’t) suggest that we “arm every teacher” as some seemed to interpret — quite the opposite, in fact.

“The selection process should be rigorous and ongoing,” I wrote.

Opening up law enforcement firearms training to properly vetted teachers and administrators who volunteer to carry concealed on campus would cost very little and have enormous potential benefit.

When a student unleashed his attack on the school in Sparks (Nev.) a couple months ago, Michael Landsberry — a Marine who would obviously be proficient with a firearm — performed his heroics without adequate tools needed to defend those young people in his care.

Teacher Landsberry died — unarmed — that day. He didn’t have to.

Think of it this way: Practically every bank in America has an armed guard on duty. Are those cash drawers more valuable than our children?

I think not.

Training for Integrated Response

In the years after Columbine, so much lip service was paid to multi-disciplinary response to school shooters that it almost became white noise. Following Newtown, many municipalities have truly embraced multi-disciplinary response beyond the merely conceptual.

An active-shooter training at Pompano Beach (Fla.) High School was designed to evaluate the multi-disciplinary, multi-team, coordinated response to a group of gunmen at a school.

One of the exercises at Urban Shield 2013 challenged SWAT teams to incorporate personnel from the Fremont (Calif.) Fire Department into their plans to deal with an active shooter fashioned after the April 2012 Oikos attack.

Many other force-on-force scenario training events — some have made headlines, while others have stayed below the radar — have been held at schools across the country.

Learning from the Past

When we train law enforcement officers to be safer and more successful on the streets, we frequently use past tragedy to prevent future loss. Deputy Kyle Dinkheller, Trooper Randall Wade Vetter, and other slain officers have been held up as examples as we teach new tactics.

We examine the mistakes of the past not to second-guess or armchair-quarterback, but to change our strategies and tactics accordingly.

Twenty little angels — whose parents I weep for today — will never again have the words, “You have a bright future ahead of you” spoken to them. My heart goes out to every family member who mourns the death of one of those kids.

My heart goes out everyone who has suffered from this terrible attack: the kids (and their parents) who survived but will forever bear the emotional trauma, the two adults who were injured, the first responders who worked that crime scene — some of them for days on end.

Their future holds some bleak days, and I’m hopeful they have the strength and support to endure despite the pain.

I’m hopeful too, that we can use the past to pave a future in which no other parent or person shares their despair.

In my heart I hope that’s possible.

In my head I know it’s not.

Some evildoer is out there, right now, plotting, planning, and preparing his attack on our kids.

So, what are we doing about it?