Impact projectiles are generally accepted as “contemporary” tools of the police trade today and as such, most agencies that deploy them give significant thought to training and preparing officers in their use. Some have deferred to manufacturer-based programs, while others have focused on independent courses such as those provided by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP). Regardless of the training origin, common themes have been found in programs that yield the greatest potential for positive outcomes in the field, including:

SAFETY PRIORITIZATION:

Successful students understand that the operational environment is not a level playing field-at least as it relates to an officers authority to take direct action to benefit one person at the possible expense of another. Contrary to media fables, everyone isn’t created “equal” when it comes to police use of force. An officer is empowered from a legal, moral, and ethical perspective to use force when necessary and appropriate, to achieve a legitimate operational objective based on where an actor fits into the safety priority “food chain”. The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) model policy on impact projectiles specifically addresses this issue in the following manner:

“Tactical decisions will be made based on our commitment to take appropriate action on behalf of, and in the order of, the following":

- Hostages

- Involved civilians: non-subject/suspect

- Police officers

- Subjects/suspects

Literally interpreted, officers are higher on the list than the subject/suspect involved in the event. As such, an officer has absolutely no obligation-and in fact should be outright prohibited-from endangering himself for example by trying to physically remove a knife from the hands of a suicidal suspect-as opposed to drilling him with impact rounds from a safer stand off range. The impact rounds create a greater risk of suspect injury than physical “hands on” disarming, but that is necessary and appropriate because it is safer for the officer-as it should be. Failing to grasp this foundational tactical concept is at the root of almost every “officer created jeopardy” shooting situation, and the related headaches, heartaches, and litigation that follows could all have been avoided by hammering this issue home during basic and in service training.

WHEN-WHERE:

The technical aspects of using the most common impact projectile system-the 12 gauge shotgun-are relatively uncomplicated. Officers that are pump action qualified already have the mechanical basics licked, they just need a training program that details with absolute clarity, the more complicated issues involving when to use the system, and where to aim the rounds in order to maximize the probability of a positive outcome.

The “when” is a tough call for many operators, and is best covered via straightforward policy guidelines detailed in training, followed by practical scenarios that test judgment as it relates to an officers decision and rationale to use-and equally important-not to use the device. Contemporary policy and training generally address such things in the following manner:

Officers who have completed the agency approved impact projectile training program are authorized to use such devices, in scenarios where an extended range impact would be necessary, justified, appropriate, and in furtherance of the primary mission objective. Examples of such situations include but are not limited to:

- Persons who are armed or appear/allege to be armed with a potentially deadly weapon, and refuse to comply with or submit to officer’s lawful authority.

- Persons who are threatening or actively engaging in self destructive behavior.

- Deterring and/or preventing criminal violators from committing acts of violence or property damage, in circumstances such as civil unrest where approaching the suspect is not a safe or viable option.

- Non-force scenarios such as “door knockers/window openers” on barricaded suspect situations .

These points must be further emphasized during training by critiquing situations that have occurred within the organization, and candidly discussing the appropriateness of the decisions made-or not made.

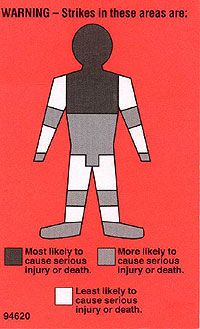

The “where” deals exclusively with aiming points, and has to do with teaching officers to balance the need to stop the behavior with the acceptability of the potential injury outcome. This topic was specifically addressed in the March 2006 issue of Policeone.com, but based on the critical role it plays in preventing negative outcomes and the value of training in this area, cannot be overemphasized. The focus must be on targeting safe body parts and as such, an easy to use training tool is the standard agency baton chart. Officers should be told that as with a conventional baton, aiming points vary based on the circumstances presented . In cases where the potential for death or serious physical injury would not be acceptable, they should consider targeting areas such as:

The “where” deals exclusively with aiming points, and has to do with teaching officers to balance the need to stop the behavior with the acceptability of the potential injury outcome. This topic was specifically addressed in the March 2006 issue of Policeone.com, but based on the critical role it plays in preventing negative outcomes and the value of training in this area, cannot be overemphasized. The focus must be on targeting safe body parts and as such, an easy to use training tool is the standard agency baton chart. Officers should be told that as with a conventional baton, aiming points vary based on the circumstances presented . In cases where the potential for death or serious physical injury would not be acceptable, they should consider targeting areas such as:

Front:

- arm below the elbow and above the hands (fingers should be avoided)

- thigh

- leg below the knee

Rear

- buttock

- arm below the elbow

- thigh

- leg below the knee

Officers should further be instructed that they are authorized to consider targets in higher injury risk areas such as the solar plexus and abdomen, if the use of force is justified based on the circumstances and efforts to subdue the suspect using a lower risk area are:

- Ineffective

- Inappropriate (the officer is unable to see/target the safer area, but the shot needs to be taken to stop the behavior-example: A person cutting off body parts with a knife, who is positioned where all you can see/target is the solar plexus. This is potentially more dangerous, but the shot needs to be made because death will likely occur if the self mutilation is allowed to continue).

- Too dangerous (A subject armed with the machete is advancing on less lethal officers, while a cover officer is preparing to use deadly force. A shot to the solar plexus may be the only chance this suspect has for survival).

Intentional shots to the neck or head shall be avoided unless defending against a direct deadly threat, and a fatal outcome would be acceptable. Shot bag deployments to the chest should be avoided due to the general lack of effectiveness and history of fatalities following impacts to this area.

An issue that is often overlooked but closely related to targeting error involves rapid follow up or “double tap” shooting techniques. This concept is well thought out and appropriate in the deadly force environment, but has absolutely NO PLACE in the less lethal realm. If you want to absolutely-positively guarantee that you will not hit your intended target, fire two bean bag rounds in rapid succession. The first will hit where you aimed (assuming you did your part and used quality ammunition at an appropriate range), the suspect will unconsciously and often violently react to the impact by MOVING, and your second round will hit whatever body part has now moved in front of it. Remember, the impact rounds move at a snails pace compared to conventional ammunition, and the suspect definitely will move enough between rounds to cause major point of contact errors. Several critical skull fracture injuries and one fatality have been connected to this phenomenon. As such, officers must ensure that proper sighting is acquired after each shot, to prevent accidentally striking an area (or person) due to the suspect moving/falling into or out of the path of a round fired “in volley”.

This is addressed by the outright prohibition of “volley fire”, and alternately directing officers to use the following engagement cadence:

- Appropriate initial verbal dialogue

- Sight the proper aiming point

- Fire a single round

- Evaluate result

- Verbal challenge

- Reacquire sights/aiming point

- Fire a single round

- Verbal challenge

This continues as long as necessary/productive/appropriate, with special consideration being given to alternative tactics when it appears obvious that the technique is not working, and the injury risk of multi volleys outweighs the value of continuing the deployment. It is also important to note that multiple shooters create the same problem as “volley fire”, and guarantees that areas of the body will be hit that were not intended. Should this occur, a serious injury or fatal (unjustified) outcome could follow. One shooter, directing well aimed fire as outlined above, best serves this process.

VALIDATION OF LEARNING

Such discussions must then be followed by legitimate testing processes to validate that learning has occurred and/or offer opportunities for clarification/remediation. This involves both a written test, which documents material committed to memory and subject to recall, and a scenario based test, which documents practical decision making skills. The written test should address issues relating to policy and procedure, with special emphasis on those critical areas that impact safe and effective use. The scenario based test is where the “rubber meets the road”, and assists in determining whether an officer can apply the knowledge committed to memory, in a practical and realistic way. Be forewarned: practicals are time consuming and labor intensive, which is why many agencies avoid them. Likewise, they are the best method of shaping performance in the field, and preparing officers for the task at hand. Even a basic overview of practical scenario based training goes beyond the scope of this article. Contact Policeone.com writer Ken Murray (Training at the Speed of Life) for specifics concerning his area of expertise.

Such discussions must then be followed by legitimate testing processes to validate that learning has occurred and/or offer opportunities for clarification/remediation. This involves both a written test, which documents material committed to memory and subject to recall, and a scenario based test, which documents practical decision making skills. The written test should address issues relating to policy and procedure, with special emphasis on those critical areas that impact safe and effective use. The scenario based test is where the “rubber meets the road”, and assists in determining whether an officer can apply the knowledge committed to memory, in a practical and realistic way. Be forewarned: practicals are time consuming and labor intensive, which is why many agencies avoid them. Likewise, they are the best method of shaping performance in the field, and preparing officers for the task at hand. Even a basic overview of practical scenario based training goes beyond the scope of this article. Contact Policeone.com writer Ken Murray (Training at the Speed of Life) for specifics concerning his area of expertise.

Safe and effective impact projectile programs are not rocket science, but they do require attention to detail in critical areas such as those outlined above. When properly used, they have been proven life savers in countless incidents. Likewise, when used in situations outside of contemporary thinking and training, they have resulted in death and serious injuries on both sides of the badge. Officers who would like an instructor lesson plan addressing the topic outlined above should send an email request to the author at lesslethal@aol.com.