BY AMY DRISCOLL, The Miami Herald

The sketches that struck fear in Miami still stare down from billboards, oversize reminders of the year the Shenandoah rapist prowled the streets near Little Havana.

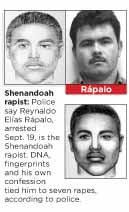

But with the arrest of Reynaldo Elías Rápalo more than a week ago, it quickly became apparent: The billboard drawings didn’t resemble Rápalo strongly enough for people to recognize him.

“Obviously, the drawings were not as effective as we would have liked because, for people who knew this person, the sketches didn’t remind them of him,” Miami police Lt. Carlos Alfaro said. “It’s just a tool that we use to help us. In some cases it does. In this case? Not really.”

HARM AND GOOD

Composite sketches have been used in many high-profile cases -- the Unabomber, the Tamiami Strangler, serial killer Ted Bundy among them. But some national law enforcement experts worry that the drawings, culled from the fallible memories of traumatized witnesses, can cause as much harm as good.

A textbook example: the mistaken identity case of Eddie Lee Mosley and Jerry Frank Townsend.

Townsend, an odd-jobs worker with a child’s IQ, spent two decades in prison for a series of rape-murders in Fort Lauderdale he had confessed to under interrogation.

In 2001, DNA tied Mosley to the crimes. Townsend was released from prison, and Mosley was sent to a mental hospital. The reason police initially arrested Townsend? He fit the composite.

“Composites can be helpful, but we think at other times they can be harmful as well,” said Gary Wells, a psychology professor at Iowa State University who studies composites and police lineups.

‘If an inaccurate composite is published, it can lead other witnesses to think the composite is actually who they saw -- and that can become a `get away free card’ for the perpetrator,” he said.

In the case of the Shenandoah rapist, police ended up relying more on a driver’s license photo of a man who resembled the rapist than they did on the sketches. DNA, fingerprints and Rápalo’s confession linked him to seven rapes.

But police say they aren’t backing away from composite sketches -- with good reason. The drawings can help raise public awareness, function as a rough outline of the criminal and sometimes lead to an arrest, experts say. South Florida police departments frequently borrow the services of the two forensic artists employed by Miami-Dade police. Miami-Dade is one of a handful of departments in the nation that employ artists full time.

“The sketches work differently for us than they do for the general public,” Alfaro said. “We look for individuals that match certain features. It’s just a guide.”

BUILDING BLOCK

Even defense lawyers say sketches alone aren’t a problem as long as prosecutors use them as a building block for their cases, not the main evidence.

“What I have to do as a defense lawyer is determine, was the arrest based simply on a sketch or is there independent corroboration,” said Milton Hirsch, a Miami defense attorney considered a national expert on criminal procedure and evidence.

“If there is other evidence like DNA, the sketch instantly becomes the least of my problems,” he said.

Sketches are not a uniquely American law enforcement technique. In Indonesia, for example, four men were charged with the bombing of a Bali nightclub last year, picked up, in part, because of their resemblance to composite sketches.

JUDGMENT CALL

Deciding whether to release a sketch is a judgment call every time, said retired FBI supervisory agent Gregg McCrary.

If the sketch is a good likeness, the offender might be scared enough to stop, at least for a while. But if it isn’t? “It can embolden the offender, make him feel invulnerable, that he’s beating everyone,” McCrary warned. “And that’s not the message you want to send.”

He cited the case of Wesley Dodd, executed in Washington state in 1993 for killing three boys.

Dodd, who had been molesting children in a park, stopped after seeing fliers that showed a composite drawing of the perpetrator.

By chance, police interviewed him one day in an unrelated incident. The officers failed to make a connection between Dodd and the composite, McCrary said, giving Dodd a feeling of invincibility.

“And so he went right back at it,” McCrary said.

The accuracy of a composite isn’t all luck, though. The skill of the artist makes a big difference, experts agree.

Samantha Steinberg, of the Miami-Dade police forensic art unit, drew the most recent sketches of the Shenandoah rapist, the ones credited by some in the investigation as looking the most like Rápalo. Her work, she said, is a combination of artistry and therapy.

“Going through the composite process allows [the victim] to take control of the situation . . . and take some of the power back,” she said. “They’re also able to get this image out of their head and let it go and let us take care of him.”

Sometimes she can tell how closely she’s nailing the resemblance by the reaction of the victim assisting her.

“Victims will get really emotional,” she said. “I’ve literally had victims leave the room because they couldn’t stand to be there with the image.”

USEFUL TOOL

Sometimes, the sketches simply work to narrow the field of possible suspects.

“You’re eliminating thousands of people. You’re eliminating a lot of races and ethnic backgrounds,” said John Valor, who began working for Miami police as a crime scene technician in 1972 and retired in 1991 as a supervisor in crime scene investigation.

The sketches are only as good as the information gleaned from witnesses, he said, and eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable. “You’re relying on people’s memory under very traumatic conditions -- this is not a photograph, it’s a sketch,” Valor said.

The accuracy of the sketch, he said, comes down to fallible human beings. “People have an extremely difficult time at even describing their mother.”