By Dave Spaulding

Click here to subscribe to Law Officer Magazine

You may have to poke ‘em in the eye

Law enforcement is a profession of close contact with the public at large. To do their job, police officers must constantly come within double-arm’s length of other people - an area I call The Hole. In this region, officers face their greatest peril, but there’s just no way for them to avoid coming in close contact with citizens and suspects. Imagine the outrage that would result from officers standing back 30–40 feet and yelling to a citizen, “Sir! Please remove your identification and throw it over here to me. I don’t want to get too close to you for officer safety purposes!” As for suspects, you can’t properly take them into custody in a secure manner without laying hands on them and placing them into handcuffs. We’ve known for a long, long time the single most dangerous moment for any officer is when the first cuff is placed on the suspect’s wrist.

So, it should come as no surprise that the majority of shootings involving police officers occur at distances of less than 10 feet, with many of these inside The Hole. That said, you’d think a major portion of firearms training would take place at similar distances, but nothing could be further from the truth. The reality: Training for close-quarter shootings proves difficult and potentially dangerous, so many agencies just don’t do it.

PHOTO DAVE SPAULDING Close-quarter confrontations will occur within double-arm’s length and may involve multiple suspects. This range scenario simulates such a confrontation. |

Over the past five years or so, I’ve thought a lot about how we in law enforcement should prepare for extreme close-quarter shooting situations. I’ve researched what’s being accomplished in this area across the country, and I’ve interviewed officers who’ve been involved in such situations. Be it good or bad, I’m also a product of my own experience, and I can’t help but compare methods currently being taught to what I’ve gone through first-hand. After three decades of law enforcement, much of it in assignments such as SWAT, narcotics, undercover operations and night-watch patrol, I have a fair amount of personal experience to draw from - something I find lacking in some of the instructors and researchers currently establishing training doctrine and trends.

With this in mind, and at the risk of poking some of current training doctrine in the eye, I’ve decided the best way to prepare for a close-quarter shooting situation is to keep things simple and don’t over-complicate the process, because history has shown that simple works best. Trying to invent a technique for each possible situation is tempting, but we all know this is impossible. And, considering the majority of police officers will train/practice only when they’re scheduled for in-service training, it makes sense to follow the SIG principle: Simple Is Good.

Simple Combat Techniques

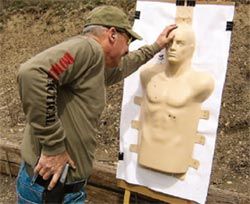

Practicing palm-heel strikes against this TAC-MAN target is a great way to incorporate live fire into closeconfrontation training. |

The first thing you need to understand: The firearm is not the solution to every confrontation, even if deadly force is justified. When your confines are The Hole, introducing a gun may result in the suspect seizing it and using it against you. My opinion - based solely on personal experience - is that when confronted at double-arm’s length, you need simple-to-perform (but quite effective) hand-to-hand combat techniques, such as knee, elbow, palm-heel, forearm and head-butt strikes. Unfortunately, these skills are being replaced with more complicated subject-control techniques, such as wristlocks, pressure points, grappling and arm-bar takedowns. This is regrettable, because to disengage and create the space needed to employ a firearm, you must make aggressive strikes to soft parts of the body.

In addition, note these three points:

• You cannot draw a holstered pistol against a weapon that is already drawn;

• Action will always beat reaction unless you do something to distract the attacker; and

• If a gun or knife is already in play, the weapon must be the focus of the attack, not the individual.

If you can deflect the weapon, then maybe, just maybe, you can bring your sidearm into the fight. But this assumes the officer has solid holster skills. Many officers currently walking the street can’t draw their handgun from their threat-level 2, 3 or 4 security holster in less than five seconds, which makes bringing it into play in such a situation doubtful. Yes, weapon retention is important, but not at the expense of being able to deploy your best weapon quickly when needed.

Commit to Do Harm When Necessary

You can move a three-dimensional mannequin in different directions to simulate human movement during a closequarter gunfight. |

Early in my career, I rode in the back of an ambulance with a very large female mental patient being transferred from a hospital to a mental health facility. Somewhere along the route, this “lady” became upset and, amazingly, broke loose from her restraints and attacked the ambulance attendant. His response was to jump out, while the driver actually sped up in an effort to get to the hospital. While I was thrown around inside the rear of the ambulance, the patient went for my holstered Smith & Wesson Model 66 revolver. The fight was on. I tried all of the various holds and pressure points I’d been assured would turn a combative suspect to Jell-O, but none of them worked. I was amazed at the amount of strength this woman possessed as she threw me back and forth. She finally latched on to my gun and wouldn’t let go, and I knew it was only a matter of time before she got control of it. I solved the problem by executing a super secret, Ninja-like, spec-ops move known to very few people on the planet - I poked her in the eyes. She let go of the gun, grabbed her face and the fight was over.

Very early in my life, I realized people must be able to see and breathe in order to do anything physical; interrupting either will affect your opponent’s ability to function. This tactic served me well on playground bullies. At the same time, don’t think that doing this will be as easy as it sounds - your opponent’s head and neck will tend to stay in constant motion. Strikes and claw-like strokes to the face and neck are easy to execute and require little training, but they do require a level of commitment. You must be willing to hurt your opponent - something that many people, even when faced with injury or death, just will not do. Remember: You must be an active participant in your own rescue.

Using dummy, Airsoft or SIMUNITIONS guns, person-on-person fighting proves the best way to train for close-quarter gunfighting. Only human interaction can show how hard it is to use a gun at double-arm’s length. |

Some will say face smashes and forearm strikes to the neck don’t work in real fights, but you’ll have to prove this to me. I performed the technique three times (besides my little ambulance ride) during my career, and it worked every time. And keep in mind, I was never trained in the maneuver beyond learning to straight-arm while playing football. All three incidents involved attempts to disarm me, and each time the technique gave me the time and distance I needed to draw my sidearm and control the situation. Had there been a weapon involved, I would have either tried to gain distance (non-firearm) or deflect the weapon before launching a counter-attack. Is a face-rake guaranteed to work? Nope - there are no guarantees in a fight - but I’m willing to go out on a limb and state that if you make solid contact with the eyes, nose or throat, you’ll get your opponent’s attention.

Live-Fire & Simulation Training

Officers will likely require unconventional shooting methods when in The Hole. |

Once you achieve a solid understanding of basic striking techniques, I recommend you undertake both live-fire and simulation training (Airsoft or SIMUNITIONS) to better understand the dynamics of close-quarter shooting. Such training won’t take the form of square-range drills, but will require you to exit your normal comfort zone and tussle (actually get quite physical) with other officers while trying to deploy their sidearm from the holster. This is quite a challenge, and needs to be experienced to be fully understood. After dry drills, you’ll need extreme close-quarter, live-fire training. The live-fire drills I like to use in training require three-dimensional targets, such as the TAC-MAN or full-size mannequin from Law Enforcement Targets (www.letargets.com). These targets allow you to make physical contact in a realistic manner, and they can move side to side in a human-like fashion. It’s much more difficult to strike a target that’s wobbling back and forth. And, requiring the shooter to fire the gun underneath their face is an educational experience in itself. Add lateral and rearward movement required to disengage from a real fight, and you’ll achieve some very realistic live-fire training. Go slow in the beginning, and be careful, because serious injury can/will result when performing such drills if you’re not totally focused on what you’re doing. However, the return you’ll achieve from the effort is well worth it.

Dave Spaulding is a 28-year law-enforcement veteran, retiring at the rank of lieutenant. He currently works for a federal security contractor. He’s worked in all facets of law enforcement - corrections, communications, patrol, evidence collection, investigations, undercover operations, training and SWAT, and has authored more than 600 articles for various firearm and law enforcement periodicals. He is also the author of the best-selling books Defensive Living and Handgun Combatives.