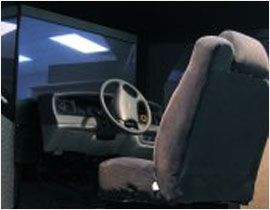

Driving Simulators have existed for over 30 years. Many of us remember the small computer screen and steering wheel from school driving courses. While the technology has grown tremendously in the airline and trucking industry, until recently it has had a difficult time transitioning to the field of law enforcement. The last decade has seen just a few police departments utilizing simulators to hundreds of them utilizing the technology to train LE in a wide variety of driving scenarios and skills.

Permission of the Rural Law Enforcement Technology Center |

The growing trend of simulator use appears to have occurred for several reasons. As the technology of LE simulators improved combined with an increase in the awareness that the dangers of LE driving brings, departments looked to driving simulators to either supplement their current track program or to develop a program where none existed.

While one simulator can cost in excess of $90,000, the initial cost of a driving facility including land, cars, surface, etc. can exceed millions of dollars. While simulators can never replace the actual driving a track can provide, they are increasingly being used to fill the gap of cash-strapped agencies and those larger agencies that cannot place every officer on the track for a full day.

The Philadelphia Police Department implemented training simulators in 2001. While the classroom and track will always be an integral part of their training program, the simulators have been relied on heavily since their inception. Philadelphia Lieutenant Robin Hill, who heads the department’s accident prevention unit, says that their simulator training is not punishment for officers. “We want to pull officers up here to keep their skills fresh,” he says. “It’s done in a proactive fashion.”

For the PPD, the results have been a complete success. From 1998 to 2003, police-involved collisions decreased by 23%, with another 1% decrease in 2006. Lieutenant Hill cites the simulators as making the difference, and knows that for collisions to remain low, his simulator program must continue to evolve.

While Lieutenant Hill is preparing to add new scenarios to his six-year-old simulator system, he does acknowledge the technological advancements since their program began: “The new simulators seem to be leaps and bounds above what we have here, and obviously the closer to reality we can get without crashing, the better it is for our officers.”

While a simulator could never replace vehicle training, it does have several advantages. First off, large-scale feasibility: The major companies offer over 100 pre-packaged driving and terrain scenarios—everything from a high-speed pursuit of a bank robber to driving in the desert can be done with the control of a keyboard.

If a particular officer has experienced difficulty in a specific aspect of driving, a scenario can be customized to meet the needs of that officer or the agency. For instance, the San Antonio Police Department used their simulator to address their high number of intersection collisions. In one year, the number of intersection collisions declined 75%. The simulator was credited for the reduction. While San Antonio had an aggressive track training program, they simply could not give adequate intersection training without placing their officers and instructors at extreme risk.

The efficiency of simulators is what instructors tout the most. The National Highway Transportation Safety Board states that one hour spent in a simulator is equal to eight hours on a driving track. Anyone who has sat in a simulator can attest to the intensity and speed of its decision-making scenarios.

Best of all, you don’t have to stand in line to use a simulator, and instructor critiques are immediate. Scenarios can be easily replayed, letting the officer learn from his/her mistakes and successes. During the training, an instructor can easily evaluate several aspects of driving, including the correct use of emergency equipment, steering, braking and intersection clearance.

While it may be difficult and time-consuming to teach a new recruit basic skills such as shuffle steering on a track, a cone course can be set up on a simulator and those skills can be introduced prior to the recruit even getting into a car.

Despite the success, many agencies remain hesitant to move forward with a driving simulator program. It is indeed smart to be cautious and do the necessary research so your department doesn’t wind up out a chunk of money, with a failing simulator program.

Keep an eye out for this month’s Police1.com product newsletter for a list of the best simulators. Coming March 22nd.

Captain Travis Yates commands the Precision Driver Training Unit with the Tulsa, Okla. Police Department. He is a nationally recognized driving instructor and a certified instructor in tire deflation devices and the pursuit intervention technique. Capt. Yates has a Master of Science Degree in Criminal Justice from Northeastern State University and is a graduate of the FBI National Academy. He moderates www.policedriving.com

, a website dedicated to law enforcement driving issues. He is available for consulting and may be reached at policedriving@yahoo.com.