Editor’s Note: While you’re reading the below article by PoliceOne Contributor Kyle E. Lamb, you may want to consider checking out the upcoming course schedule posted at Viking Tactics. If you’re an active-duty officer within a reasonable distance of the San Francisco Bay area, there are still some slots available for the course taking place April 4-9, 2010, at the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office Regional Training Center.

Anyone who has participated in a decent number of tactical entries knows that these operations are high risk. Risk is a given and it is every entry team member’s job to work toward minimizing that risk while still accomplishing the team’s assigned mission or task. One of the biggest risks a tactical entry team will face is movement through a hallway. Hallways, typically devoid of cover or concealment, present the same tactical problem to an entry team as a large open field might present to a squad of infantry advancing toward an objective. We learned in Army Special Operations that to expose a team too long in either situation is inherently risky. We also learned — through experience and more than a little bit of blood shed — that most of the basic principles which apply to a squad attempting to cross an open field also apply to the entry team making its way down a hallway.

Tactics should be principle-based rather than based on one specific technique for each task. In other words, an entry team — just like its infantry counterpart — should have basic tactical principles that they do not violate, and should then apply techniques that both adhere to those tactical principles and address the context of the individual situation. For example, infantry soldiers understand that massing fires can be effective but massing personnel is often deadly.

Thus, basic principles such as dispersion, overwatch, and movement from cover to cover must be rigorously observed even as the individual tactical circumstances dictate how they are applied. It’s the same for movement in a hallway.

Example: Forward Security

No matter the particular technique for negotiating a hallway, someone on the team must always have cover to the front toward the most likely potential threat. Another example may be that no one on the team may enter a room alone — he must always have a teammate with him. These principles are the framework within which the team should establish their specific techniques. Too often teams develop overly-detailed techniques for accomplishing simple tasks. Consider these two examples, both of which apply directly to team movement in a hallway.

First, the act of opening a door and entering a room: a team moving down a hallway may have a method whereby they move the entire team past a closed door for the purpose of making it easier to open. This makes sense if the team’s main task is simply to open one door. If, however, their mission is to find and eliminate a threat, it becomes less sensible for them to focus so much time on the simple task of opening a door.

A second example is the method by which a team may prepare to move from one room to the next: Many teams place one person out in the hallway who acts as a ‘Hall Boss’, and they rely on him to decide which room gets cleared next. Just as our infantry squad would not leave someone exposed in the middle of an open field to control movement if they were faced with a threat, the lone teammate in the hallway is too vulnerable when he’s by himself with no teammates to cover his movement.

Maximized Flexibility

Entry teams often train to use very specific techniques to accomplish particular tasks in an attempt to reduce the need for leaders to exercise a great deal of control under stressful conditions. In some cases, this can certainly be effective. But if this is the only method the team knows, they can easily become bogged down when the situation encountered doesn’t match the conditions for which they have trained. If individuals within a team have not been trained to think ahead and act, they may wait on a decision from the team leader or hesitate while they struggle to apply an inappropriate technique rather than moving forward and trying to find and eliminate the threat.

Teams with methods that force them to focus on their “proper” movement techniques instead of on finding and eliminating the threat may find themselves in positions in which their carefully-rehearsed techniques do more harm than good. Simply put, a good movement formation does not always equal a good fighting formation. Our infantry squad marches as a column across open fields when there is no threat because it is the quickest means of moving from point A to point B. That does not, however, make marching the best means of fighting across the same field. The fighting formation should be the goal of any team, because its focus is on the threat and the most efficient way to eliminate that threat.

|

As mentioned above, the Hall Boss technique is widely used, often in conjunction with another widely used method, the Diamond Formation. The Diamond continues to proliferate despite the fact that it’s mostly a movement formation, and does not work well to fight from if the need arises. The single point man seems like a good idea, until someone shoots back at the team. At this point, the lead man will invariably go to a wall, thus blocking the ability of the two flank officers behind him from returning fire.

We teach a fighting formation that also happens to work well during movement through a hallway. Our whole methodology, whether it’s applied to hallways, individual rooms, or entire structures, is based on simplicity and mastery of basic principles that apply regardless of the specifics of the threat. Simple principles are the framework within which we establish our techniques, which are widely applicable, proven in combat, and effective.

A thorough discussion concerning this formation, and of our other entry tactics and techniques, normally requires hands-on walk-through and demonstration, but we’ll attempt to lay out some of the fundamentals below. A brief explanation of our philosophy may help to frame the discussion.

Encourage team members to recognize the need to act. We should all promote problem solving on our teams and in our departments. We believe that all team members should know when a task needs to be accomplished and that anyone on the team can (and should) do it. If all team members are trained to a common standard, any of them should be interchangeable within the team. They should react to what their teammates do, by covering sectors or rooms that are not already covered, or by lining up at the back of the stack in order to enter the next room. In practice, this can mean any of the following:

• The #2 man in the stack, inside any given room, can make the determination when to commence movement into the next room or hallway

• Anyone can be the #1 man at any given time, and that this #1 man may be the #3 or #4 man into the very next room

• The #1 man can sometimes open the door to initiate movement into a room — it’s not necessary (and sometimes ridiculous) to move a teammate into a vulnerable position — by taking this time we may jeopardize the safety of the team as well as exposing a team member to an uncleared door (bad guys shoot through closed doors!)

• The decision for which room to clear next can be made from inside the room instead of out in the hallway, before movement out of the room commences — just as our infantry squad plans its movements from one piece of cover to another rather than stopping in the open to do so

|

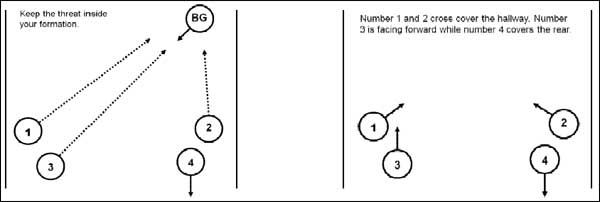

Applying the above principles, replace the Hall Boss and Diamond Formation with a Fighting Formation. The Hall Boss technique leaves one man alone in the hallway and exposes that person to excessive risk with no extra teammate to help him if he makes contact. Instead, use a fighting formation where the decision on where to go next is made by the #1 man, who is still in the last cleared room looking down the hallway toward the un-cleared threat. This keeps the whole team out of the hallway, conceals their position from any suspects, and allows them to communicate and fight when required. In other words, the hallway is treated the same as the open field our infantry squad must maneuver across and the current room becomes its current position of cover.

Doors are opened as they are reached, from the near side, and with as little choreography as possible. Again, this is done to minimize the point of maximum vulnerability when the team is tightly packed in the hallway. The #1 man either opens it into the room and leads the team in, or opens it out into the hallway and holds it while they enter (he then becomes the #4 man). If the door is locked, a breaching tool is used.

Front and rear security should always be maintained. Upon exiting the room, the #1 and #2 man reestablish security posture before the team comes into the hallway, and then the entry to the next room is made as quickly as possible so as to minimize exposure. As with an infantry squad, make every effort to provide security from a static position in order to ensure that you can accurately engage threats. The #2 man, who is now rear security in the hall, is afforded this opportunity while he waits for the rest of the team to exit the room and move toward its next objective.

Simplified Choreography

Reading through the above examples, it should be plainly obvious that adhering to the recommended basic principles, teams can reduce the amount of choreography required to execute basic building clearing operations. We’ve instructed teams on the techniques built around a basic set of principles as part of our fighting formation training and over the course of an afternoon, teams can become highly proficient in developing tactics and techniques that adhere to these principles and greatly reduce the risk they face while maneuvering through buildings.

During our tactics classes we are often asked the question, “These techniques are fine, but what do you do for a barricaded suspect scenario?” or, “How about a hostage rescue? Or a high risk warrant service?”

Our answer is always the same: Apply the same principles for every mission, change the specific technique or alter the speed at which you operate as the situation dictates. Since the principles are not violated, these techniques work. This is true regardless of the size of the structure or the number of team members that are available for the entry. A simple technique, applicable to most situations, is the preferred methodology. Simply, it is easier to train and remember for each member of the team, allows for a simpler plan during an actual operation, and is more efficient in every aspect.

More importantly, these techniques are the same techniques used outside of the structure as well. During MOUT (movement over urban terrain) movement, we use the same Fighting Formation as we use inside a structure. We treat the street as if it were a hallway and the alleys as though they were doorways.

This is not to say that we have no specific techniques; we do. The Fighting Formation is based on first, dealing with the threat, and then with the means by which we get there. This thought process allows the team members to make the decision on which technique to use, and rely on proper training to ensure that his teammates will, a) recognize what he’s doing, and b) step in to help, or follow him.

The Fighting Formation

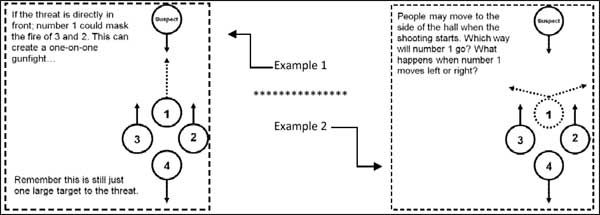

The Diamond Formation is a movement formation and not a Fighting Formation. The Diamond Formation does not allow for a planned position for each shooter. Specifically, where will each team member go and who will shoot when contact is made? If contact to the front is made, only one shooter can engage the threat. Principles specify that we should have two to three weapons on every threat; however with the Diamond Formation this is not possible. If the shooters to the left and right of the Diamond start engaging the threat, where will the front officer move? Although we have had officers tell us that they will stand in the center of the hall and return fire, claiming that they will not move to the wall for cover, a more innate response would be to seek cover. In a hallway the only place to go is the wall (usually en-route back to a cleared room). Therefore it is best to have the team’s fighting formation place them along the wall in the first place.

We train teams to move in two columns, along the walls, so that the lead officers can cover each other as they move. This provides the added benefit of enabling at least two team members to cover a sector and engage the threat if needed instead of only one, as in the Diamond Formation. See the diagrams below.

Rolling Thunder

The Rolling Thunder technique allows the team to start on the walls and stay on the walls and move very quickly to a crisis site in a large structure. It also allows the front two shooters to have interlocking fields of fire, and normally allows the 2nd officer on one or both walls to be able to engage a threat as well. Not only does the technique allow for interlocking fields of fire, but very large fields of fire. This is especially important when dealing with all the angles you are forced to deal with inside a building or when moving through an urban environment.

Cross coverage allows shooters to comfortably and quickly move, while not being surprised at the last moment by a threat very near their location. This technique is better experienced than briefed. Most significantly, as stated earlier, this technique uses human nature, and is one technique that works well in almost all situations. If room entries are required, this technique also places the shooters where they need to be to make the entry, versus a tight formation that now needs to be adjusted for entry.

As an entry team member or patrol officer, ask yourself this: “Would you rather fight against one adversary or many?” Obviously, most people — to include the bad guy — would choose to fight only one. The Rolling Thunder technique discussed above forces an armed suspect to engage multiple officers instead of just the point man of the diamond. If you are in the Diamond Formation you are one target. If you are in the Rolling Thunder Fighting Formation you are splitting the hall, you are already where you want to be when the shooting starts, you have interlocking fields of fire, you are massing fire not forces, you will normally have two weapons on every threat, and you are in a position to quickly move into a room to eliminate a threat or to seek cover. The bad guy has to have unbelievable luck, or engage several targets. Which position would you rather be in? At the end of the day, success in a deadly encounter is measured not by how well you performed your rehearsed formation, but by eliminating the threat.

Bottom line: You must be in a formation that allows you to complete your primary mission — which is to eliminate the threat.

SGM Jason Beighley (Ret) collaborated with Police1 Contributor Kyle E. Lamb in the creation of this article. Jason served in the US Army for 24 years, over 20 years in US Special Operations. Jason served in numerous combat operations to include Mogadishu, Somalia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Jason is a Primary Instructor for Viking Tactics, Inc.