Editor’s Note: We welcome to our roster of writers Sgt. Bill Campbell. We asked Sgt. Campbell to begin his column, “Bringing the Street to the Range,” with an item that examines the unique tactical challenges present when the gunfight involves a motor officer. We do this because the memory remains raw of Sgt. Mark Dunakin, 40, and Officer John Hege, 41, who died on the streets of Oakland in March 2009. We will never forget.

Not all cops are the same, not all environments are the same, and not all gunfights are the same, yet so often we find ourselves doing the same qualification style drills in a square, static firearms range. The truth is, there is no perfectly flat, straight, red firing line or berm backstop at the Wal-Mart in “Your-Town, USA.” When the gunfight comes to your officer at your Wal-Mart, what training will he/she have received that prepared him for the fight he is now having. We cannot bring the sterile, controlled qualification environment to the street; we must “bring the street to the range.”

Bringing the Street to the Range is NRA LEAD’s philosophy that the goal of LE firearms training should not be just to meet a qualification test standard, but to prepare the officer for the environment where he/she must fight and win. Over the past several years, several instructors across the nation have sought new ways to analyze the conditions officers must fight and find a way to adapt specific training to those environmental parameters.

Police1 has asked me to deliver an occasional article on these concepts, and this is the first in that ongoing effort. To begin, this article will look at some of environmental factors that can affect the Motorcycle Officer. I’ll then offer some basic training principles and offer some suggestions for motorcycle based firearms training you can bring to your department.

Last order of business before I begin: I want to hear back from the officers who choose to read my columns, so add your comments below or send me an e-mail.

The reality of the Motor Officer’s potential gunfight

Motorcycle Officers are some of the most highly trained and motivated personnel we have. To say that a “Motor” is a different breed is an understatement. Motors are hunters who endure harsh temperatures, wear extra equipment, and usually find themselves alone when dealing with offenders. At any given time they may find themselves dealing with “Soccer Mom” or they may find themselves dealing with a hardened career criminal like the suspect who attacked the Oakland Motor Officers murdered this last spring.

In analyzing the Motor Officer’s environment a few things become apparent.

1. Motors wear more protective equipment than the average officer. In some seasons that equipment might simply be a helmet, glasses and a set of gloves. But when the temperatures fall at night or during the winter, that equipment may be heavy leather jackets, boots, extra underclothing and even special heated gear plugged into the motor for extra warmth.

2. Motors consistently do the same muscle movements almost to a ritual. Ask any motor officer what the steps are when he stops and dismounts the motor and he will be able to tell you step by step each process he does and why. This muscle memory can become so engrained that it could be used against him in certain fighting environments

3. Motor Officers are “multitaskers.” All of the hands and feet are involved in multi-tasking to operate the motorcycle safely. Anyone who rides, know this fact; but add in the radio, lights, siren, tether lines to the helmet and the ever present knowledge that the person you are approaching may wish to kill you, and these tasks can quickly become overwhelming under stress.

4. Unlike officers in patrol cars who can stand behind the doors of their squad, Motors have very limited cover in their working environment. The officer is generally on the motor, standing by the motor, walking to or from the suspect vehicle or at the suspect driver’s door. None of these locations offer much cover, especially if he is attacked by more than one suspect.

Several years ago Dr. Enoka cited three causal factors in the unintentional contraction of a human hand which could result in an accidental discharge of a firearm.

Those factors were:

1. Sympathetic reflex: The tendency of the fingers of one hand to unintentionally contract when the other hand grasps intentionally.

2. Balance disruption: The tendency for the fingers to contract when balance is lost (likely to grab at something in an attempt to catch the body).

3. Startle effect: The fight or flight response causing the fingers to contract.

Now for a moment, imagine a scenario where a motor officer is dismounting his motor as a suspect suddenly charges at him or displays a deadly weapon. He attempts to draw his firearm to defend himself while his leg is coming over the back of his motorcycle, so his balance is potentially disrupted. One hand is grasping the firearm while the other is grasping the handlebar balancing the weight of the bike and possibly a brake or clutch so he now has a potential sympathetic reflex. Finally, the attack from the suspect is sudden and chaotic and the officer recognizes an impending chaotic attack is imminent, so there could be an argument that he also has a startle effect.

As you can see, we have a “perfect storm” of all three factors occurring simultaneously for the officer as he tries to stop, get off the motor and defend himself. Can he effectively fight? Might he have an unintentional discharge? What training has he had on the “range” to prepare him for this “street” problem?

Training principles identified

This was exactly the circumstance my agency looked at a few years ago and in working closely with my agencies Motorcycle Officer’s, we recognized a few principles of training:

Principle 1: The Officer cannot fight and ride the motorcycle at the same time. He must make a conscious choice to do one and abandon the other if he is to succeed at either. Despite what we see in Hollywood movies, there are simply too many skills involved in riding a motorcycle to concentrate on the principles of marksmanship and adequately fight simultaneously. The officer must make a conscious decision to either ride and escape or commit to the fight.

Principle 2: The Officer cannot dismount and draw a handgun at the same time without a realistic expectation of unintentional discharges and the potential for innocent people endangered. Because of the realities of Dr. Enoka’s research, officers must operate the handgun deliberately either from the motionless saddle or ditch the motorcycle entirely to focus attention and skills to the effort of shooting. Rounds errantly fired because of accidental discharge are both a great liability and also a waste of time while trying to win a fight.

Principle 3: Motor Officers must train with the equipment they use daily to gain a realistic proficiency in the environment they work. It’s not enough that the officer is a well trained rider and a well trained gunfighter; there must be a smooth transition from one to the other which allows the officer to minimize his risk and quickly overcome his aggressor. This means that he must train in the uniform he actually works in and train in any of the positions or phases of the attack he might find himself. These include:

• Stopping the motor

• Sitting in the saddle

• During the dismount

• Beside the Motorcycle

• During the walking approach

• At the suspects vehicle

• On the ground beside or even partially under the motor

In-service firearms training solutions

Once the principles are recognized, the task of the firearms instructor is to create firearms training drills that safely place the officer in the same environment that he would find himself on the street.

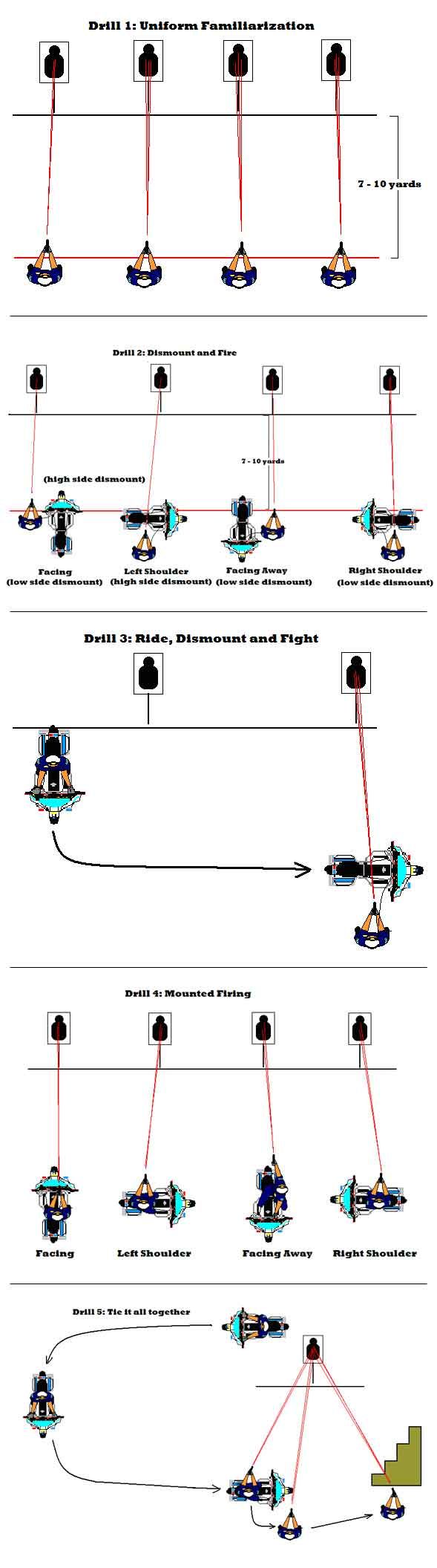

Drill 1: Full Uniform Familiarization

Recognizing that the most consistent factor in all the potential scenarios is the officer and his uniform, we start with firearms training in his actual motor uniform. For this drill, the standard line drill recreating multiple ranges, multiple targets and multiple skills used for all patrolmen are perfectly applicable except that the motor should perform them with full uniform equipment.

He needs to experience the limits of his mobility with a helmet, heavy coat and riding boots and the loss of dexterity with gloves.

Officers should practically fire fast, accurate hits with multiple weapons handling tasks such as draws, reloads, and malfunction clearing with lateral movement and “pivots and turns” incorporated. Instructors who train SWAT officers regularly will already have a laundry list of drills because the SWAT officers must also train similarly in their heavy gear.

Once the principles are recognized, the task of the firearms instructor is to create firearms training drills that safely place the officer in the same environment that he would find himself on the street. (PoliceOne Image) |

Drill 2: Static Dismounting Drills

This line drill is the next step from the previous line drills. The key here is to allow the officer to start in the saddle with the engine running as though he was stopped at a light. When the target turns (or command of the instructor), the officer must concentrate on dismounting as quickly as possible and reposition himself using the motor for partial cover and return fire to the target.

Based on the second principle, the officer must complete the dismount before the draw and return fire.

After a few repetitions the instructor should then have the officers turn the entire motor a different direction to simulate the attack coming from a different direction. This is where that muscle memory I mentioned can become an issue. If the officer always dismounts off of the low side or the high side, he may be actually stepping into the problem. The instructor uses this opportunity to train the officer to incorporate his dismount to use the minimal cover offered by the motor.

Throughout these drills, the officer should avoid extra movements that waste time, such as removing a helmet or gloves or even disconnecting a radio tether from the motor; his goal should be to return fire as quickly as possible once safely dismounted.

Drill 3: Stop, Dismount and Fire

Unlike the past two line drills, only one officer fires at a time and the others rotate into this drill. In this drill, we take the skills from the last drill and add actual riding into the equation. The individual officer rides his motor around the range in a figure 8 pattern or around the targets as instructed and on command; the officer must stop the bike, safely dismount and return fire as quickly as he can.

After hitting the target, the officer returns to the motor and rotates out of the drill. As the officers rotate through repetitions, the instructor should choose different location from which to have the officer engage so that he must engage the target from all angles (in front of him, to his left, to his right and from behind him).

Drill 4: In the Saddle

It would be great if the officer was always able to safely dismount and defend himself, but what if the attack comes too fast or he is simply unable to get off the motor due to the environment. I use the example that the officer has split lanes of traffic and cars on either side of him prevent his dismount when the attack comes.

It’s times like these that my good friend Jeff Hall of the Alaska State Troopers teaches in his class called “Finish the Fight” that the officers first instinct must be to simply fight back and in referring to the firearm, he uses the mantra, “Get it out, Get it on and Get it over!”

In this case, the officer must be able to quickly draw while in the saddle and return fire prior to dismounting. Once again we use a line drill in which the officers are on the motor and now they simply draw and return fire when the target turns, being cognizant of their own windshield, radio tethers and their own bodies. As before, every few repetitions, the motorcycles are turned 90 degrees so that the officer must simulate attacks from all angles. The officers will be holding the bikes upright with their stance while firing, so a slow progression in speed is fine and attention must be given to not muzzling other officers or the officers themselves during the drill.

Drill 5: Tie it All Together

Now that the officers have experienced fighting from their feet and from the motor from multiple angles, we need to tie all the skills together. For this drill we return to the same format we used on Drill 3 with one officer participating at a time.

We add a few pieces of random cover around the range as well. This time as the officer is driving around the range in a figure 8 or large circle, when the target turns, the officer stops the motor and immediately draws and fires from the saddle hitting the target 2-3 times. Now with the motor stopped, he simply side steps from the motor allowing it to drop onto the bars and crouches or kneels behind it to deliver a few more hits from the partial cover of the motor.

Finally, he disconnects any radio tethers quickly and moves to the nearest safe cover on the range and fires 2-3 more hits from its protection. The goal of this drill is to allow the officer to move through all the potential phases of the gunfight from the saddle to partial motor cover to movement to superior cover.

Some officers may be reluctant to allow the bike to drop and lean over onto the bars but that is exactly what they were designed for and the reality is that the motorcycle itself is of little concern in a fight for your life. Once again, as officers rotate through the drill, the location and angle of the attack should change to allow the officers the reality that the attack can come from any angle.

Drill 6: Scenario-based Drills

I’m a firm believer that realistic live fire range drills are essential but they are the boxing equivalent to punching a heavy bag. To completely understand the reality of a physical fight you have to spar with another living, breathing moving attacker who wants to harm you. To close the training gap, instructors should consider scenario-based training to make the practical drills come to life. Instructors can use force-on-force equipment or even an interactive video simulator to create scenarios where the suspect attack comes from different locations at different phases of the traffic stop. As always, all safety protocols must be paramount.

Start with student officers conducting normal traffic enforcement stops. The suspect might attack prior to the officers dismount, during the officer’s initial approach, at the suspect’s door, while the officer is writing the ticket, during a simulated arrest or even from a person who is not the driver. At some point, you may even have the scenario start with the officers leg pinned under the bike as though he has crashed or has been rammed by a vehicle and is down. While this is a worst case scenario, it certainly has merit. Can the officer fight from the ground, free himself and radio for help? The instructor’s imagination is the source for great training in this realm once the principles are trained.

Final thoughts

In my own agency, the motor officers are very well trained on how to ride their motorcycles and are some of the most competent officers I’ve ever had the privilege to work with. All of them told me they felt this type of range training was absolutely essential for a front line motor officer and encouraged me to share it with other agencies. Our classes, including a short lecture and live fire drills, took about three hours for a 3-4 man class and each officer fired about 150 rounds. Scenario based training could last several hours longer but does not necessarily have to be done in the same training session.

For those concerned with the safety aspects of bringing Motorcycles onto the range or perhaps don’t have access to a range that will allow this type of training, consider doing all the drills with Air-soft or FX guns in a parking lot with a few cardboard targets on stands. Those who absolutely don’t want to scratch their beautiful BMW or Harley-Davidson motorcycle on concrete might be more willing to do so in the middle of a large grass field using an Air-soft gun. The range and the actual duty firearm are not the essential ingredients to this training, the student and the motorcycle are.

All of the drills mentioned are simply my way of implementing the training principles and are offered as an example; each instructor should carefully tailor make the training to meet the needs of their own officers and agency.

At the end of the day, the goal is to recognize that the Motorcycle Officer’s world is a little different than the average patrolman. Bringing the street to the range for our Motors is an investment in their survivability — a small investment that reduces liability and just might save their life someday.