Blacksburg Capt. Bruce Bradbery scooped the students up one by one and loaded them into his gold Explorer. With lights and sirens on, he drove over sidewalk curbs and lawns to reach the ambulances.

By Sari Horwitz

The Washington Post

Graphic: Inside Norris Hall

Read P1 News Report: Virginia Tech Shooting April 16, 2007

BLACKSBURG, Va. — “We’ve been hurt,” the voice whispered, terrified, into a cellphone.

On the other end of the line, Virginia Tech Police Lt. Debbi Morgan could hear gunfire. It was so loud that it sounded as if someone was shooting right into the receiver.

“Where are you?” Morgan asked, doing her best to stay calm.

“Two-Eleven Norris Hall,” the voice said so softly that it was obvious to Morgan that the person did not want to be heard.

There’s a shooting! 211 Norris Hall! Morgan shouted to two dispatchers. Happening now.

“Are you still there?” Morgan asked.

Silence.

Gasping for breath.

Pop. Pop.

“I can’t talk,” the voice said.

“Keep yourself safe,” Morgan said. “We’re sending people.”

“Please hurry,” the voice whispered.

* * *

The windows of room 204 of Norris Hall where students jumped to escape while Virginia Tech professor Liviu Librescu was shot while blocking entry by Virginia Tech gunman Seung-Hui Cho.(AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) |

Nineteen-year-old Emily Haas’s call to Morgan helped unleash Virginia’s largest police and emergency response since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the Pentagon. The 911 call came at 9:43 a.m. April 16, just as Seung Hui Cho’s Norris Hall rampage began, and Haas and Morgan stayed on the phone until Virginia Tech and Blacksburg police officers rushed into Haas’s classroom and found Cho dead. Interviews with Morgan, Haas and more than three dozen police officers, emergency responders and federal agents provide for the first time an inside look at the enormous rescue and investigative effort that followed the shootings.

They also reveal details about what happened inside Norris as Cho killed 30 people, then himself. Even before he chained the doors at Norris and began his rampage, Cho had reconnoitered the Gothic-style building. The morning of the shootings, he poked his head into several classrooms before the attack. With methodical precision, he moved from room to room along a second-floor hallway and shot anyone who moved with his two handguns. When he was done in each room, he closed the door behind him. Then he went back to rooms where he’d already been, found students who were still alive and executed them at point-blank range. Of the 30 people who died at Norris, 28 of them were shot in the head. Cho shot some four or five times.

Within eight minutes of Haas’s call, Blacksburg and Virginia Tech police broke into Norris Hall. They worked frantically to save students clinging to life. Medics performed triage and rushed victims to safety as SWAT teams moved through the building to confirm that Cho had acted alone. In the critical first 20 minutes, when ambulances could not pull close to Norris Hall because they hadn’t been given the all-clear by SWAT teams, one officer placed wounded students in his sport-utility vehicle and ferried them over sidewalks and lawns to get to the ambulances, parked blocks away.

* * *

The newly repaired door of room 204, which now only has a bolt lock and no doorknob. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) |

Emily Haas, a French major from Richmond, was lying against a wall, partially behind a desk, in the back of her classroom. With her blue eyes squeezed shut, she held a cellphone to her ear with her right hand. Around her middle finger was the silver “angel band” of her Pi Beta Phi sorority. She was wearing jeans, an old yellow T-shirt of her mother’s and a new pair of brown Sperry Top-Siders; a baseball cap covered her blond hair. The smell of burnt gunpowder swirled around her as a silent Cho fired his handguns.

“Try to stay calm,” Morgan, 42, a mother with three young children, told Haas. “Ease your breathing.”

Two minutes into the call, Morgan asked Haas whether she still heard the gunshots. Yes, Haas said, but they were farther away. The gunman had spent 120 frightening seconds in her classroom, then gone next door.

“Stay under the desk,” Morgan said. “Keep talking to me. We’re hurrying. They’ll be there in a minute.”

|

|

“Thank you.”

Silence.

“Are you there?” Morgan asked.

“Yeah, I’m here,” the voice whispered. “We need an ambulance.” Students were bleeding all around her. She heard moaning. Haas opened her eyes slightly, saw a shell casing and closed them. Was the door locked? Morgan asked. It doesn’t lock, Haas replied.

Then, as if out of nowhere, the gunshots became loud again. Pop. Pop. Pop.

“He’s in here,” the voice whispered. It was 9:48. Cho had retuned to Room 211. He was shooting quickly, walking down aisles cluttered with book bags and bodies. He went to many students who were breathing, aimed at their heads and fired. Bullets ricocheted off walls. Haas tried to play dead.

Pop. Pop.

Morgan heard Haas scream. A blood-curdling, hysterical scream.

“I just got hit,” she said.

A bullet had struck the back of Haas’s head.

Sharp pain.

* * *

As Morgan tried to keep Haas calm, Virginia Tech and Blacksburg police officers were desperately trying to get into Norris Hall two floors below. Since the Columbine shootings, police across the country have trained to respond to an “active shooter” by entering a building immediately.

Blacksburg Police Sgt. Anthony Wilson ran with four officers to the front double door. But the door was chained from the inside. They heard glass breaking, people screaming and shots being fired. They ran to the northwest corner of Norris and met up with other officers, some in SWAT gear. They tried the door there; it was also chained. “Shoot the chain,” they yelled almost in unison. One aimed a shotgun and tried, but no luck. He shot again. It wouldn’t budge.

On the phone, Morgan heard another loud gunshot. And another. She heard the girl’s breathing quicken. “He’s reloading,” Haas said.

“Okay, there’s units there. Stay calm. Try to stay calm. Ease your breathing.”

ATF officers look into cars parked near Norris Hall on the campus at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va., on Monday, April 16, 2007. (AP Photo/The Roanoke Times, Eric Brady) |

Haas’s breathing slowed.

“What’s your name?

“I can’t talk.”

Pop. Pop. Pop. “Still shooting in Norris,” Morgan screamed to a dispatcher as Haas screamed.

Lt. Curtis Cook, leader of the Virginia Tech SWAT team, heard the shots and looked up at the gray limestone building to see if he could spot the gunman. The officers moved to a big wooden door next to the chained one. It was locked with a deadbolt. An officer shot through the lock and pushed the door open, then the group ran inside through a mechanical shop. It was quiet.

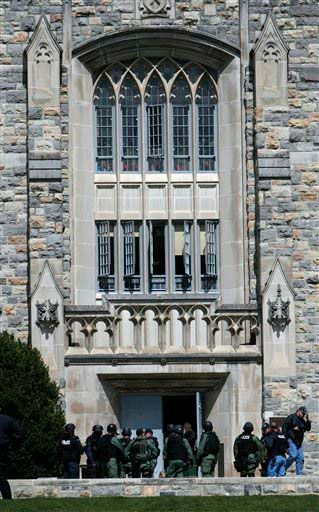

Law enforcement officers are assembled outside Norris Hall during a lock down on the Virginia Tech Campus in Blacksburg, Va., Monday, April 16, 2007. (AP Photo/The Roanoke Times, Eric Brady) |

They split up. Some, including Wilson, the Blacksburg SWAT team leader, started up a staircase. Cook and his group moved down the first-floor hall, checking classrooms in an “emergency clearing” tactic, and headed up another staircase, at the other end of the hall, so they would have both sides of the second floor covered.

At 9:51, as Cook and Wilson moved up opposite stairwells, they heard a gunshot.

Where was the gunman? they wondered. Was he with hostages? Which classroom? Which floor? How many gunmen were there?

* * *

The 9:51 shot echoed inside Haas’s classroom. It was so loud that it seemed as if it were right next to her. Through Morgan’s 15 years as an officer, she had dealt with difficult situations. But nothing like this.

“Stay calm,” Morgan said.

Neither of them knew it, but Cho had just put a 9mm Glock to his head and pulled the trigger. Haas’s eyes were still closed, her head wounds were starting to throb. Am I going to die? I must not be dead yet if I can feel this. Was the gunman still in the room? She didn’t want to touch her head. She didn’t want to feel the bullet. She didn’t want him to see her move.

She heard Morgan in her ear: “The officers are inside, so just stay calm. Stay with me. Stay calm.”

Sirens wailed and radios blared. The officers, some in black helmets and carrying high-powered rifles, moved down the second-floor hallway. Several frightened students ran out of a classroom. Two officers helped them out of the building by walking them to the south entrance on the first floor. It was chained. One shot the chain, and the first students poured out of Norris at 9:56.

On the second floor, a team of officers moved from room to room, searching for the gunman and trying to find wounded students. Because of all that firepower and adrenaline, Cook became worried about friendly fire with Wilson’s group. So he ordered some members of his team to cover the stairwell and the others to pull back and clear the third floor’s rooms. They met up with the second team and together made their way down the second floor. Cook and four officers tried to open the door to Room 211. But they couldn’t. Something was blocking it. They yelled: “Police! Open the door!”

The police are at your door, Morgan told Haas. Can you get up and open the door?

When she opened her eyes and stood up, she found herself in the middle of what looked like a combat zone. Around her, 11 of her classmates and her teacher were dead. Five others were badly wounded. She didn’t know whether the shooting had lasted five minutes or an hour. Cho, his face covered with blood, was lying in front of the classroom near the door. But she didn’t look. She moved forward, dazed.

Blocking the door were two bodies with ghastly head wounds: One belonged to her beloved teacher Jocelyne Couture-Nowak, who would greet students with “Bonjour!” and sing French songs during class, and the other was a classmate’s. Holding the cellphone in one hand, she tried to pull the door. It cracked a little. Then shut. She felt weak and dizzy. An officer radioed to Morgan, who was still on the phone. Tell her to step back, he told Morgan, and he pushed hard. Haas was face to face with SWAT officers pointing guns. “Hands up! Show us your hands!” one said. They couldn’t take any chances. Haas wearily tried to raise her hands.

Her hair was disheveled and filled with bullet fragments. Blood dripped down the right side of her face. A Virginia Tech sergeant pulled her out and walked her down the hall. You’re going to be okay, he said.

On the first floor, Haas saw Wendell Flinchum, who had been Virginia Tech’s police chief for only four months. Flinchum and Blacksburg Police Chief Kimberley Crannis had run into the building from the other side. They couldn’t shoot the chain because faculty were at the door, desperate to get out. One officer tried to rip the door off its hinges as Jason Dominiczak, 22, a senior and volunteer medic, ran for bolt cutters from an emergency rescue truck. They opened the door a few inches, cut the chain, let the staff out and flooded the building. Early that morning, Crannis and Flinchum had called in SWAT teams in case they needed to serve warrants in the 7:15 a.m. shooting of two students in a dormitory across campus. Those SWAT officers were able to get to Norris Hall first, just three minutes after the first 911 call.

Flinchum, who once attended classes at Virginia Tech, put his arm around Haas and helped her out of Norris. “You’re safe now,” he said.

* * *

Police opened every door and knocked down locked ones. As officers passed students who were able to walk out, they asked: “One shooter? Two shooters? What does he look like? What’s he wearing? Where is he?” One gunman, they replied. Black T-shirt. Asian.

At 10:08, officers got their answers: An Asian male with a massive head injury was on the floor of Haas’s classroom. He was wearing a black shirt, cargo pants and an orange-and-maroon Virginia Tech baseball cap. Two guns were at his side, one loaded. Despite his wounds, they could not be sure he was dead and took no chances. They handcuffed him. “Shooter down,” a sergeant yelled.

But almost at once, the officers remembered, they wondered whether there were more shooters. One person couldn’t have done all this. As they continued to open each classroom door, the officers were met with unspeakable horror. Lifeless students in jeans and tennis shoes sprawled on the floor and under overturned desks. Blood everywhere. On the walls, the desks, the floors.

One student’s head rested on the wooden laminate top of her desk. It looked as if she were taking a nap, except for the pool of blood underneath. Some bodies lay on others. One student was shot and fell on another. He was shot again, and a bullet went through him and into his classmate. There were head wounds, leg wounds, bodies riddled with bullets amid the clutter of books, notebooks, cups, school papers, wallets, calculators.

Through it all, Crannis was struck by the utter silence. “You would never have known that there was anybody in the classrooms,” she recalled.

Crannis didn’t know whether some students were alive until she touched them. The ones who responded only whispered. Some were too wounded to talk; the others had survived by playing dead and were too scared to stop. The first student who asked for help was under a body.

Officers opened the door of Room 207 and saw a wounded student with his hands on top of his leg resting on a desk. Show us your hands, they yelled. The senior held up his hands, and blood spurted all over. He had been shot twice in his leg, one bullet piercing his femoral artery. Virginia Tech officer Jaret Reece quickly cut an electrical cord from a projector, ran to the student and began fashioning a tourniquet.

Dominiczak and medic Brad Privett leapfrogged from room to room, applying bandages, inserting IVs and providing other first aid. Officers tried to calm students. The scene was like a battlefield: They made rapid decisions about each one’s condition, yelling colors that told the officers what to do: Red meant life-threatening injuries. Yellow was the next level -- unable to walk. Green was the walking wounded. Black meant the student was dead.

The student with the tourniquet was red. Even though Haas had been struck in the back of the head, she was green.

* * *

Ambulances were still blocks away. Not every room and hallway had been thoroughly searched. Blacksburg Capt. Bruce Bradbery, a 25-year police veteran and a deacon in his church, made a split-second decision. The badly wounded students could not wait.

With the help of Flinchum and Blacksburg Police Capt. Donald Goodman, Bradbery scooped the students up one by one and loaded them into his gold Explorer. Goodman shielded one, fearful a shooter could be inside and might fire. Bradbery put those with the worst wounds in the front seat so he could steady them with one arm and told the ones he put in the back to hold on tightly. With lights and sirens on, he drove over sidewalk curbs and lawns to reach the ambulances. Bradbery drove back and forth through the blustery wind and snowflakes to get and deliver more students, including Haas. As she sat in the back, she worried she was getting blood in his nice car.

One girl told Bradbery that she was afraid she was going to die. “You’re not going to die,” he said. He knew she was scared. He was scared, too. “Ambulances and hospitals are waiting for you.” At 10:30, when the police announced that the building was safe and ambulances drove up, Bradbery took a minute to call his wife. “I’m okay,” he told her, “but whatever you’ve heard, take the worst case, multiply it by 20 and that’s what we’re standing in.”

In an ambulance, Blacksburg EMT worker Sue McGann-Osborne gave Haas a warm blanket and water. She helped her call her mother. It was 10:38 and the world had not yet heard of Norris Hall.

* * *

Once the search-and-rescue operation was over, local police turned the scene over to the Virginia State Police. Agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives also were there. In addition, 100 state troopers were on their way. Rushing down Interstate 81 alongside them came sheriff’s deputies and police and ambulance units from across southwestern Virginia.

When Col. W. Steven Flaherty, the state police superintendent, arrived from Richmond before 2 p.m., scores of officers were photographing, documenting and searching for evidence. They could hear student cellphones ringing. And ringing. Loved ones were desperately hoping for an answer.

One of the toughest tasks was identifying the victims. Their IDs, if they had them, were in backpacks and book bags scattered throughout the classrooms. Officers would later have to ask some parents about unique marks on their children’s bodies.

Bart McEntire, the head of the ATF’s Roanoke office, walked into the bloodstained hallways of Norris about 3 p.m. Since the morning, his agents had been helping to evacuate and secure more than 100 buildings on the 2,600-acre campus and respond to bomb threats and other reports of shooters. Crime scene technicians gathered ballistic evidence -- 174 spent casings and 203 live rounds. ATF Agent Terry Henderson searched through a black-and-gray backpack by the second-floor water fountain. A claw hammer, a folding knife, a straight-blade knife and a receipt from Roanoke Firearms were in the bag. McEntire sent an agent to the gun store to find out who bought the weapon.

Visitors stop by a makeshift memorial made up of of stones for the Virginia Tech shooting victims on the Drill field of the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg, Va., June 13. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) |

McEntire knew his most important task was to determine whether the earlier shooting at West Ambler Johnston dormitory was connected to Norris. He dispatched Agent Tom Gallagher to the ATF laboratory in Beltsville to compare evidence from each scene.

It was too windy for the governor’s plane to take him, so Gallagher carefully sealed the guns and casings into a box and got on the road about 4 p.m., driving 90 mph with lights and sirens on much of the way. The pressure was intense. Investigators had not identified the shooter or matched the crime scenes. Firearms examiners met Gallagher when he arrived at the ATF laboratory three hours later.

Walter Dandridge, the examiner who matched the bullets in the Washington area sniper case, got to work. Peering through a microscope, he began to examine the lands and grooves in the bullets from Virginia Tech in a process called “ballistics fingerprinting,” which matches distinct marks on recovered bullets to a particular gun.

Back in Blacksburg, frantic parents, siblings and spouses at The Inn at Virginia Tech waited for word about their loved ones. The task of telling the parents about the deaths of their children fell to the two police chiefs -- Flinchum and Crannis. Flaherty would join them later. For hours, the chiefs, accompanied by chaplains, entered private rooms to meet with family members. Both had given death notifications during their careers. But on this night, they would enter those rooms over and over and over again.

As the grim notifications continued, investigators inside a makeshift command center on the first floor of Norris learned that the Roanoke Firearms receipt had been preliminarily linked to 23-year-old student Seung Hui Cho. The paperwork he filled out to buy a 9mm Glock on March 13 listed his immigration and naturalization number. Soon, they were able to get a fingerprint from immigration records. They matched that to a print from Cho taken from the morgue. FBI Supervisory Senior Resident Agent Kevin Foust sent an agent to Cho’s family in Centreville and contacted the FBI’s Seoul office.

About 2 a.m., a weary Tom Gallagher returned to Norris from Beltsville and McEntire told him to go home. About 3, as Gallagher was driving home, he got a call. The bullets matched. Cho’s 9mm gun was tied to both crime scenes.

* * *

Police officers visited Emily Haas at Lewis-Gale Medical Center in Salem, where she was treated. Cho’s bullets had grazed, but not entered, her skull. Forensic nurses took pictures of her wounds and collected the bullet fragments from her hair as evidence before police asked her to tell them what she remembered.

Her 911 call had been critical to officers. By staying on the phone, she had given them details about what was happening inside Norris when they were locked outside.

The officers who entered Norris Hall the morning of April 16 underwent stress debriefing sessions to deal with what they saw. Crannis, Wilson and others visited hospitals to see the students they had rushed to safety. McEntire went to church one night after everyone else had left and sat in a pew, alone with the lights off, and prayed. In a heart-wrenching return to Norris, Flinchum took some parents of students who died to the second floor.

Until about a week ago, Bradbery could not go back to Norris. “Trying to make sense of senselessness,” he said. “By God, you can’t do it.”

Haas returned to Virginia Tech with her mother to thank the lieutenant whose calm voice she heard over the cellphone. They hugged. The wounds on the back of Haas’s head remain tender, but she feels better and is trying to move on. Debbi Morgan said seeing Haas’s dimpled smile helped her begin to heal from the effects of what she’d heard unfold in Room 211.

Neither of them wanted to hear the tape of their 911 call.

Staff researcher Julie Tate contributed to this report.

Copyright 2007 The Washington Post