The 2016 film “Patriots Day” sparked controversy for omitting Officer Dennis “D.J.” Simmonds, who died a year after the Boston Marathon bombing from injuries sustained during the Watertown shootout. Since then, his family has worked tirelessly to share his story — a story of courage, sacrifice and a push to recognize him as the fifth victim of the Boston bombing.

Roxanne Simmonds will never forget the call. Her son answered while sprinting toward Boylston Street. She could hear the strain in his voice, his heavy breathing.

“Ma, I’m OK. But we are under attack.”

Bombs had exploded at the finish line of the Boston Marathon. Roxanne was in Tampa — over a thousand miles away from her son, her baby, her D.J. She knew the risks that came with being a police officer, but she never imagined terror would strike the heart of the city that her son called his beat. She never imagined her son would have to brave that terror head-on.

“We have to take our city back,” D.J said. “We can’t let people do this to our city.”

Born a guardian

From a very early age, Dennis “D.J.” Simmonds wanted to be a hero. While growing up in the city of Randolph – just a short drive from Boston – he and his younger sister Nicole would don capes and pretend to be superheroes. They even gave each other names. Nicole was CC. D.J. was Tunga Man.

“D.J. would say ‘Dun da da dah! Tunga Man!’ and go running down the hall with his cape,” Nicole said. “To this day I don’t know how that name came about.”

Like all superheroes, D.J.’s instinct was to watch over those around him. He was fiercely protective of Nicole, and his role as a guardian didn’t stop with her.

“He wanted to be everyone’s big brother, not just mine,” Nicole said. “He was a big brother to all of my friends. He was a big brother to our family. He was a big brother to the community.”

“He was a protector. It was so evident,” Roxanne added. “ When he was a teenager, he trained our dog to do perimeter searches. It was just the weirdest thing. It’s almost like it was in his blood.”

D.J. was also fascinated by another type of guardian: first responders, particularly cops.

“He wanted to be a police officer before he could talk it seems like,” Roxanne said. “He was fascinated by blue lights. Whenever he would be in the car seat, he would just go crazy when he saw either a fire truck or a police car going by.”

D.J. held the profession in the highest regard. It was honorable to be a cop. Everyone looked up to them. They protected other people. Despite Roxanne’s attempts to persuade him on a different career path – her dream was for him to be an attorney – D.J.’s drive to be a law officer only grew stronger with age. He fell in love with the film “Bad Boys.” He’d joke that he was Will Smith.

A ridealong during high school sealed it; D.J. was going to chase his dream of being a cop. And not just any cop – he wanted “First in the Nation” on his badge.

Boston Strong

D.J. loved Boston. As he was finishing his criminal justice degree at Lasell College, his family moved to Tampa. But D.J. wouldn’t go. Boston was the only city he wanted to patrol. He felt a sense of duty to the place he considered his home.

“I can tell you, I did everything I possibly could to get him to leave Boston, and he was drawn to that city,” Roxanne said. “He loved everything about that area. He would do anything to protect the city, anything at all. It was so important for him to be there and to help make it a safer place.”

D.J. was the youngest officer in his graduating class. He started his career in Brighton – a college area – but wasn’t happy with simply handing out parking and traffic citations.

D.J. was thrilled when he quickly moved to an urban area of the city, Mattapan. He and his partner felt like they were truly making an impact — tackling tough issues like the gang problem in the neighborhood while making the effort to get to know the community on a personal level.

Ever the guardian and leader, D.J. was always on the lookout for opportunities to set a good example, whether it was trying to guide an arrestee to a better path in life or connecting with the youth in the area.

Once, when D.J. responded to a residence and found a child watching TV during school hours, he took the time to speak with him about the importance of getting an education. Another time, in the dead of winter, D.J. spotted two kids out in the cold and bought coats for them with money out of his own pocket. He wanted to show something positive to everyone he interacted with – to send a message that police officers were out there to do good and keep the community safe.

“He knew that life was not always fair for some of these individuals that he was in contact with, but he wanted to show them that there is a different way,” Roxanne said. “He and his partner received so many accommodations for taking guns off the streets, and because they were young and men of color in this community, they could really make a difference. They could talk to the good guys and bad guys and keep it real with them.”

D.J.’s good work earned him a spot in the gang unit, which Roxanne says put him “over the moon.”

Warrior in Watertown

After the bombs exploded in Boston on April 15, 2013, the Simmonds family had very little contact with D.J. This was particularly rough on Roxanne, who spoke to her son every day. But they knew D.J. was on a mission. He was going to bring the criminals who carried out the deadly attack to justice.

“He told me, ‘I hope I’m the one who finds them because I have to represent for Boston. I cannot let them disrespect my city,” his sister, Nicole, remembered.

And D.J. would find them. Shortly after midnight on April 19, 2013, he was one of the first arriving officers in what would become the Watertown shootout. By the end of it, one perpetrator was dead and the other taken into custody. D.J. was in a hospital being treated for head injuries from a bomb that exploded near him. It was the middle of the night in Tampa, and Roxanne knew something was wrong.

“Around three o’clock in the morning, my husband and I woke up for no particular reason and just turned on the TV,” Roxanne said. “And when we turned on the TV, that’s when it showed all the footage of what happened at Watertown, and all of the sudden I hear somebody saying ‘Long gun. Long gun.’ And I said to my husband, ‘That sounds like D.J.’ So right away, I called him. And he was at the hospital.”

D.J. assured them he was OK. But in the months that followed his release, he felt the lingering effects of the shootout. A visit to Tampa was one of the first clues Roxanne had that D.J. wasn’t the same after what happened in Watertown.

“He was acting, not different, but just a little quieter than typical,” Roxanne said.

One day during his stay in Florida, D.J. stood at Roxanne’s bedroom door. She asked her son what was wrong.

“He said, ‘I don’t like the darkness.’ And D.J. never shows vulnerability,” Roxanne said. “Never. But he said to me, ‘Ma, when I close my eyes at night, I see the lights coming at me. When I close my eyes now, I see the bombs being thrown at me and I see the light and I can’t sleep.’”

D.J. wasn’t only suffering from insomnia. Unbeknownst to Roxanne, he had frequent headaches and ringing in his ears. He was going back to the doctor on multiple occasions. He was prescribed medication to help him sleep, but didn’t take it; he wanted to stay sharp on the job.

Roxanne says her son wasn’t sharing much of what he was going through at the time.

The fifth victim

On April 10, 2014, just a few days shy of the first anniversary of the Boston bombing, Roxanne spoke to her son by phone while he was at the Boston Police Academy gym. She was picking out an outfit for D.C., where the Simmonds family would watch D.J. receive the Top Cop award from President Obama. Although he had already received numerous distinctions for his bravery in Watertown, including the Boston PD’s highest award (the Schroeder Brothers Memorial Medal of Honor), D.J. was particularly excited about the Top Cop award.

But he never made it to D.C. D.J. fell ill during a workout and died at a hospital of a brain aneurysm. He was 28, in his sixth year on the force.

When Roxanne got word her son was in the hospital, she was still at the department store picking out her outfit. Everything moved quickly after that. There was little time to process before she was on a plane to Boston.

“When the plane landed, the pilot told everybody to stay in their seats,” Roxanne said. “‘We want to let some people off first.’ I wasn’t even thinking it was us. We walked out and when I saw the line of police officers, I knew at that time that was it. I can still see them. As soon as they opened the door of the plane they had all these officers on the jetway. I knew. God had taken our baby from us.”

When the Simmonds family arrived at D.J.’s home after leaving the hospital later that night, they saw open books on top of his dining room table. He was studying for the sergeant’s exam.

“D.J. wanted to be the chief of police for Boston one day,” Nicole said. “I mean he wanted to go all the way in law enforcement — as far as he could.”

When the Simmons family received the Top Cop award in D.J.’s honor, President Obama mistook his father for a cop. He was wearing D.J.’s badge, as he would often do after his son’s passing.

Unsung hero

It wasn’t until the Simmonds family received D.J.’s medical records that they realized his death was connected to his Watertown injuries. Thus began a years-long journey to get D.J. the recognition he deserved as the Boston bombing’s fifth victim. The family shared his story far and wide with the hope that the nation would acknowledge the officer who passed away as a direct result of protecting Boston from the terror that tried — and failed — to break the city.

Finally, in May 2015, the state retirement board recognized D.J.’s passing as a line-of-duty death and awarded his family a one-time death benefit. A state medical panel’s report, which cited his persistent injuries from Watertown, factored into the decision. Later that same year, his name was added to the BPD’s memorial wall.

“We’ve tried to do everything we can to share D.J.'s story widely now because I really do believe that his story is one of inspiration – you see a young man who was focused on a goal and was able to achieve that goal. And I think because he passed away the year after, his story wasn’t as widely told as the other victims,” Roxanne said.

When “Patriots Day” – a film chronicling the BPD’s efforts to bring the Boston bombers to justice – premiered in late 2016, the Simmonds family was forced to go through the pain of D.J.’s unsung heroism all over again. At the end of the film, a list of the fallen did not include D.J.’s name.

“We just wanted to see that he was acknowledged – that he lost his life and he fought in that gun battle,” Roxanne said. “He and his partners fought in that gun battle. It devastated us. I know it might seem petty to some people, but I just felt like I let D.J. down. He was the only Boston police officer who died as a result of that – the only one – and you didn’t acknowledge him? You couldn’t put his name on there?”

Gone but not forgotten

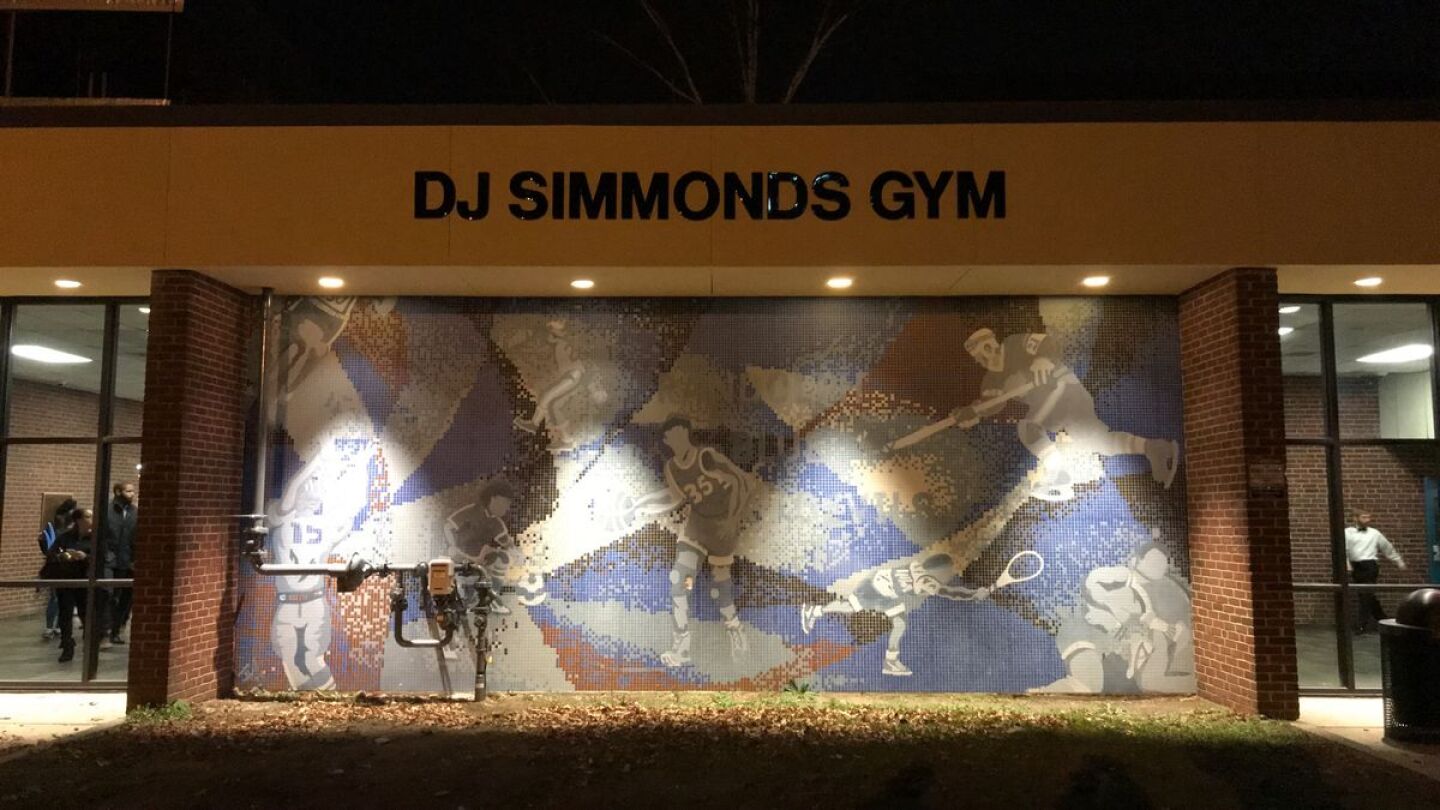

D.J.’s body is gone, but his spirit is very much alive. It’s in the Randolph High School gymnasium which was renamed in his honor. It’s in the Lasell College scholarship in his name for students pursuing a career in criminal justice and in the second criminal justice scholarship that was established for college-bound students. And it’s alive in the countless individuals across the nation who’ve reached out to the Simmonds family since his passing, touched by the story of their son’s bravery.

It’s in his uncle’s position as an auxiliary officer – a job he took in honor of the fallen hero. It’s in his colleagues at the gang unit, who carry D.J. in their hearts every day they serve the city of Boston. It’s in his badge, which his father still carries with him.

Roxanne and Nicole remember a lot of things about D.J. He was a strong athlete – captain of his high school basketball team who also had a knack for baseball and football; a sports obsessive that idolized Stephen A. Smith and could rattle off any sports statistic you threw at him; a diligent student loved by his teachers, who frequently visited his alma mater to impart wisdom to young criminal justice majors; an avid fisherman who couldn’t wait to catch the next big one with his dad; a young boy who developed a life-long love of the water and the beach during summer vacations at Martha’s Vineyard; a Bostonian who you couldn’t say a single word to when the Pats were playing on Sunday; an animal lover who’s Rottweiler, Kane, lives with the family to this day.

But what they want him to be remembered for most is the same thing he would have wanted to be remembered for: D.J. was a hero, running into that Watertown shootout just like he ran down those hallways during his childhood.

He was a protector, a guardian, a superhero. “Dun da da dah! Tunga Man!”

This article, originally published Dec. 27, 2017, has been updated by Police1 Staff with relevant information.