Editor’s Note: Suicide is always preventable. If you are having thoughts of suicide or feeling suicidal, please call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline immediately at 988. Counselors are also available to chat at www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org. Remember: You deserve to be supported, and it is never too late to seek help. Speak with someone today.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – A North Carolina officer who died by suicide in 2024 is the first law enforcement officer publicly confirmed to have suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the New York Times reported.

Gina Elliott, the widow of Brent Simpson, a longtime Charlotte Police officer, spoke with the Times about his cognitive decline. In the months leading up to his death, he’d repeated a troubling refrain almost daily: “Something is wrong with my brain.”

| RELATED: What is the prevalence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in law enforcement?

“It’s like he became a different person,” Elliott told the Times. “Like somebody I didn’t know.”

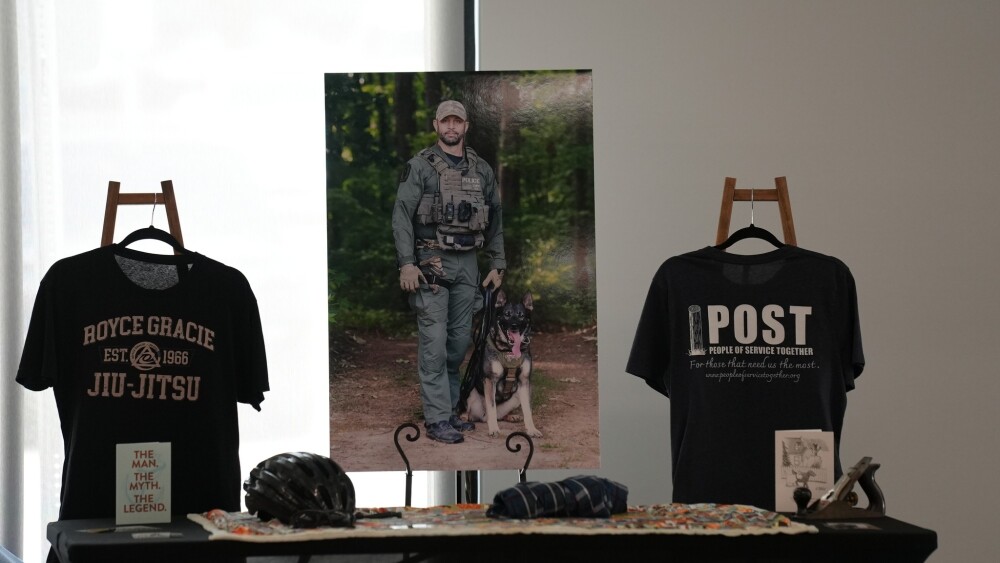

Simpson joined the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department in 2006, starting out on night patrols. By 2011, he had become a defensive tactics instructor at the police academy, teaching hand-to-hand combat to new recruits. The training, known as RedMan training, involved physical confrontations while instructors wore protective padding.

In 2020, Elliott told the Times, she began noticing changes. Simpson lost interest in his hobbies and expressed an interest in retiring early, even though he had just reached his goal of becoming a K-9 officer. He began to suffer memory loss.

Elliott documented incidents where he cried without reason, spoke of unrelenting pressure in his head and said he could no longer feel joy, the Times reports. In January 2023, Simpson attended a month-long inpatient program tailored to first responders. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and given a treatment plan.

Despite the treatment, Simpson slept no more than three hours a night. Elliott said he grew increasingly paranoid, sometimes stockpiling water and food, convinced that a disaster was imminent. After work, he’d often sit silently on the couch, staring at the wall.

Then, one July morning, Simpson kissed Elliott goodbye before heading to work. Hours later, officers came to her door.

Simpson had taken his own life in a nearby cemetery while on duty.

“I lost him twice,” Elliott told the Times. “He was gone years before he was physically gone.”

Law enforcement suicide rates are significantly higher than those of the general workforce. One study estimates officers are 54% more likely to die by suicide than the average American worker. Stephanie Samuels, a psychotherapist who has worked with hundreds of police officers, has long believed that conversations about suicide in law enforcement often overlook an important factor: the role of traumatic brain injuries.

Many of her clients report symptoms consistent with CTE, such as memory issues, impulsivity and unexplainable rage, she told the Times. When Samuels learned of Simpson’s death, she reached out to a colleague of his and helped coordinate the donation of his brain to Boston University’s CTE. Center, a leading research institution for the disease.

In 2025, Elliott received confirmation: Simpson had CTE. He is the first publicly known police officer to be diagnosed with the disease, according to the Times.

Gina Elliott spoke in depth with the New York Times about Brent Simpson’s experiences with CTE. Read the full story here.