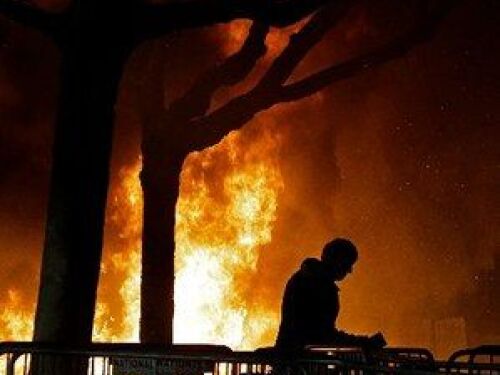

Editor’s note: The 1965 Watts Riots began with a traffic stop in South Los Angeles and quickly escalated into six days of civil unrest, fueled by long-standing tensions between law enforcement and the community. The unrest resulted in 34 deaths, over 1,000 injuries and more than 4,000 arrests.

While many historical accounts focus on the broader social and political causes, the following narrative is told by Kevin Scanlon, whose father, LAPD Officer Joseph F. Scanlon, responded to the scene that night. This firsthand reflection offers a law enforcement family’s perspective on the events as they unfolded.

By Kevin Scanlon

Sixty years ago on this date, it was a hot early evening in Los Angeles — August 11, 1965. A California Highway Patrol motor officer, Lee Minikus, was patrolling the county area around Watts when a concerned motorist hailed him and reported a reckless vehicle had passed him at a high rate of speed. Officer Minikus located the vehicle and observed it traveling 50 mph in a 35-mph zone. He activated his red lights, chirped the siren and the driver pulled over. The stop occurred on a typical suburban street lined with multiplex apartment buildings.

Officer Minikus discovered the driver and passenger were stepbrothers and both had been drinking alcohol earlier. As Officer Minikus conducted a DUI investigation alone (not safe), he had the driver perform some field sobriety tests on a nearby sidewalk. While doing so, he noticed a crowd of about 25–30 people coming from the surrounding apartment complexes, curious about the activity. Minikus radioed for two additional CHP officers to assist with the arrest. As he filled out the booking paperwork — though he hadn’t arrested the driver yet, awaiting assistance — the crowd grew to about 100 people.

The driver’s mother was able to negotiate with Officer Minikus to release the vehicle to her, since she was the registered owner (he didn’t have to during that era). But when she saw her son was going to be physically arrested, she tried to calm him down — to no avail. The driver threatened to kill the officer if he was arrested. During the arrest, the passenger and the mother of the driver fought with officers and were arrested as well.

As officers attempted to leave the area, one was spit on by a woman in the crowd. When officers entered the crowd to arrest her, some mistakenly thought she was pregnant and wearing a maternity dress. In fact, she was a hairstylist wearing a typical smock over her clothing; she had come out from her shop after hearing the sirens to see what was going on.

Little did the motor officer anticipate that his positive and proactive police work would become ground zero for what would later be known as the Watts Riots.

| RELATED: Civil unrest preparedness for your law enforcement agency

What happens next

At the same time, two officers were doing what every good cop does on patrol: driving slow enough to see beyond the patrol car, with windows down to hear danger or a call for help. These LAPD officers, from the 77th Division, were conducting their patrol duties as they had many times before when suddenly the crackle of the radio broke the silence. “Officer needs assistance” sent them racing to a call they would remember for the rest of their lives. One of those officers was my dad, Officer Joseph F. Scanlon, Badge #7735.

In the academy, you’re taught to expect the unexpected and prepare for the worst. If it turns out to be less than anticipated, you’ll likely handle it effectively and confidently. I believe the LAPD officers had learned that same lesson — but even they didn’t know this call would make history.

When my dad and his partner arrived on scene, they saw a large crowd yelling and inciting criminal behavior. The crowd was animated, defiant and angry. The CHP officers’ uniforms were ripped, and the car’s occupants were frightened. More assistance was needed to disperse the crowd and ensure the safety of the arrestees as glass bottles and concrete bricks began flying toward the officers.

The officers were able to retreat from the immediate scene, and CHP managed to protect their arrestees. The mob eventually spilled beyond the neighborhood, stoning cars and buses, overturning vehicles and beating occupants.

During the ensuing six-day riot, many gun shop owners supported law enforcement efforts by providing officers — who were short on supplies — with firearms and ammunition.

“This was a classic Gordon Graham “high-risk/low-frequency” event. But who was listening?”

History repeats itself

History repeats itself unless you’re willing to change it. LAPD, CHP and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department worked together during some of the nights to keep the unruly crowd from spilling into additional neighborhoods. Remember — there were no cellphones or Facebook then, just radio and print news, so information spread slowly by today’s standards.

Area officers continued patrolling and making arrests in and around the original location, working to contain the situation. Several hundred officers were quickly mobilized, and mutual aid could be called from across the region’s many agencies.

But just like today, the field sergeant at the scene tried to communicate the need for more resources up the chain of command — to no avail. This was a classic Gordon Graham “high-risk/low-frequency” event. But who was listening? Let me ask you: Does it sound familiar?

We all need a history lesson. On the street, we try to handle things quickly and cleanly, avoiding what’s untidy or distant — like history. We avoid the spotlight and move on to the next incident.

Meanwhile, outside commentators with no police training impugn the entire profession based on examples that feel worlds away from our day-to-day work. What’s even more disturbing is when the criticism comes from within our own agency or agencies tasked with investigating the incident.

Watts riots: Key statistics

- Dates: August 11–16, 1965

- Deaths: 34 people

- Injuries: Over 1,000 (including approximately 200 police officers and firefighters)

- Arrests: More than 4,000

- Property damage: Estimated at $40–45 million (over $400 million in today’s dollars)

- Buildings damaged or destroyed: Over 1,000

Conclusion

Amazingly, even in 1965, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office was concerned about excessive force. But upon review of the first four arrests during the Watts Riots, it was determined the officers had used appropriate force to make the arrests.

🛡️ Training tip

Use historical flashpoints like the Watts riots in roll call or in-service briefings to drive home the importance of early recognition and response to high-risk, low-frequency events. Teach the past — prepare for the future.

The laws of this country — and the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, especially on pursuits and use of force — are sound, easy to follow and straightforward to apply. You just need to be familiar with them, and thorough and articulate in your reporting and evidence.

So, police leaders, here is your mission: Learn from the past and apply what works. Get in front of the crowd and explain when an explanation is needed. If you’re uncertain about some aspect of an incident, someone in your agency can get you what you need to succeed. But above all — support your crime fighters.

| NEXT: Ferguson after-action report: Have lessons learned been applied?

About the author

Kevin Scanlon has 35 years of law enforcement experience in city and county policing. He is a California POST academy instructor, case law expert and subject matter expert in many areas of law enforcement. He is the developer/instructor of California POST’s “Drug Enforcement for Patrol” course and courses on warrant, parole and probation contact techniques and cockfighting investigations. He is an enthusiastic trainer, voiceover artist and PA announcer.

Kevin’s mantra: “Be unafraid. Command presence. The knowledge of what you can and cannot do — and embracing your authority — gives you the confidence to do this job and be successful.”