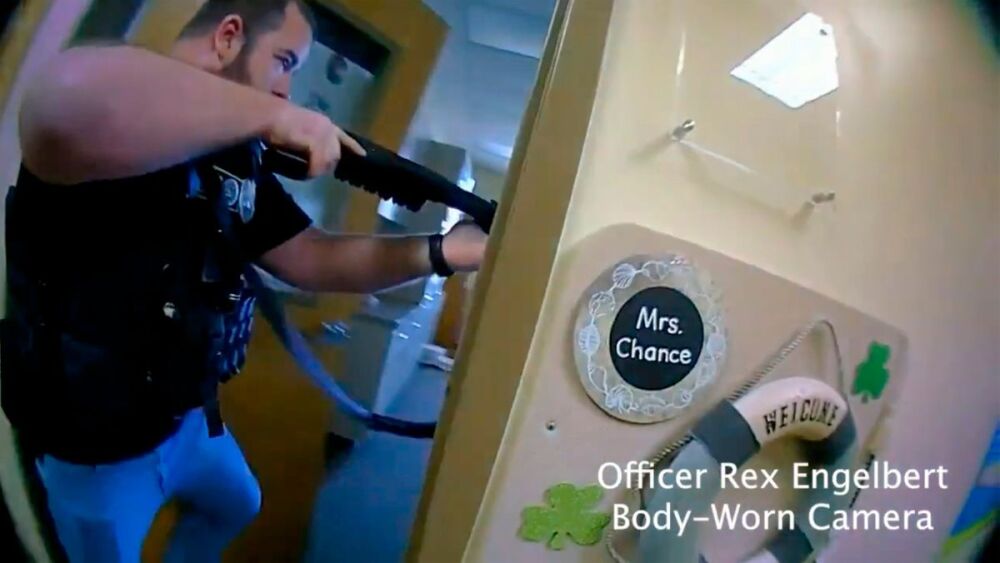

Metropolitan Nashville Police Department officers are being hailed as heroes for their fast action to find and stop an active shooter inside a Nashville elementary school on March 27. The body-worn camera footage from MNPD Officers Rex Engelbert and Michael Collazo shows a swarm of officers entering the school, moving quickly and purposefully toward the gunfire.

According to the department, both officers fired on the shooter who was killed. These officers and their colleagues should receive the highest commendations and recognition for their heroism and lifesaving actions.

The bodycam videos of the Nashville school shooting should be required roll call viewing in every department as the response of the MNPD officers is in sharp contrast to other videos from recent active shooter incidents. In these MNPD BWC videos, officers are not milling around waiting for commands, or moving away from danger to establish a perimeter. No officers are fumbling with equipment or waiting for other resources. The first arriving officers, using only the weapons and protective equipment in their patrol cars, acquired intel and moved into the hot zone.

Reducing variability in response to active shooter incidents should be a top priority for every police department from the chief or sheriff to the patrol officers and deputies who are most likely to arrive first. Here are four ways to reduce variability to active shooter incidents and make sure as many innocents as possible escape unharmed.

1. Active shooter response training

Active shooter incident response training needs to be realistic and frequent. The MNPD officers showcased constant tactical movement in small teams that can only be learned and refined through hands-on training that happens inside a school. Vocal commands were clear and there was no unnecessary chit-chat or radio traffic. When the officers confronted the shooter they acted decisively, accomplishing the only tactical objective that mattered, to stop the killing.

Watching the videos, Engelbert, Collazo and other MNPD officers demonstrate they knew what they were going to do and how they were going to do it, likely visualizing their actions as they rolled up on the scene. This is a tribute to the training they received and the seriousness with which they completed that training.

2. Active shooter response equipment

Officer Engelbert exited his patrol vehicle and had a patrol rifle in his hands in about 10 seconds. In less than a minute he received information about the shooter and he was entering the building with other officers. Other items, such as ballistic shields, helmets and forced entry tools, if available, can be carried by members of the entry team, but when seconds mean the difference between life and death, officers only need their duty weapon or patrol rifle and body armor to enter the hot zone.

3. Active shooter response policy

Policy is the guidance police officers need on what to do and how to do it. The MNPD Active Deadly Aggression Incidents (MNPD policy 14.50) makes the department’s expectation of officers clear and succinct:

It is the policy of the MNPD, based on training and experience, to permit initial responding officers the authority and responsibility to take immediate action to contain and if necessary, neutralize active deadly aggression incidents to reduce or eliminate the likelihood of additional violence or threat to life.”

Several additional pages describe the department’s procedures related to the policy, including the three phases of training for active deadly aggressive incidents.

4. Department culture and leadership

Active shooter incident response is more likely to be effective if the department’s culture and leadership uphold the expectations of policy, deliver the necessary training, and equip officers with the tools they need to accomplish tactical objectives. Officers also need to believe they will be supported by department leaders when they act decisively, competently and confidently within the department’s policies and procedures.

Is your department active shooter response ready?

Every police department has completed active shooter response training in recent years, but are you really ready? After watching the MNPD response, how confident are you in your department’s training? Are you confident in your patrol rifle marksmanship and contact or tactical team movement? Does your department policy clearly articulate the mission of initial responding officers? Finally, if you are the chief or sheriff, have you created a culture that allows officers to respond decisively, competently and confidently without fear of second-guessing or reprisal to an active shooter incident?

Let us know your thoughts on how to reduce variability to active shooter incidents and how your department is preparing officers to respond to active killers. Comment in the box below.

Police1 readers respond

- Conducting additional training with local police departments and other first responders.

-

We do not practice team concepts in active shooting cases but practice solo officers clearing for the bad guy. We don’t want to be geared up waiting for other officers to arrive and gear up. Four solo officers can clear a building faster than one team of four. And if the purpose of a team is officer’s safety, then why are we in law enforcement? I have over 50 years and notice the officers who arrive will often come up with their own version of what to do, and it often is not by the book. But training gives them options no matter the name of the procedures. We should be better trained, better equipped and better shots than the bad guy.

POLICE1 ACTIVE SHOOTER RESPONSE RESOURCES

- Download: Prevention, disruption & response: The strategies communities must deploy to stop school shootings

- Webinar: Developing effective strategies to prevent and respond to school shootings

- Nashville PD’s response to the Covenant School active shooter was ‘by the numbers’

- “SLED” lead trainer answers 10 questions about active shooter response

- ICS lessons learned from active shooter response training

- Should schools have armed staff members?

- Learn how to think in a crisis

- How a ‘culture of reporting’ can disrupt school violence

- An integrated technological approach to school attack prevention and response

- ALERRT’s Dr. Peter Blair on scene management during active shooter response

- Katherine Schweit on the progress being made in stopping the active shooter threat